The Effects of Digital Trade Agreements on Economic Relationships between Nations

Introduction

Digital trade agreements are pacts between economic players that sets clarity on the form of engagements in the exchange of technological products. The technological dynamism is associated with substantial economic benefits that foster growth, prosperity and development. A paradigm shift has manifested as the United States has continuously developed an overreliance on digital revolution precipitated by digital trade having a high GDP share. Trade agreements in the digital sector focuses on a set of provisions namely; protection of intellectual property within digital goods and services, ensuring efficient data flows within the trade. Discriminatory treatment of economic specific digital products is harnessed within the international markets (Kim, 2024). Furthermore, international market penetrations relies on the set provisions of a country’s agreements that prevent exploitative engagements.

Property risks are safeguarded in digital trade agreements and ensures that technology firms do not lose their products to their competitors without their intention. Copyrights protection is set to nurture fair treatment of cutting edge technologies hence ensuring a rigorous development of reliable associations within markets. A competitive advantage is required in the context of digital trade protective enactments. Foreign markets are deemed to have a diverse participants whose intentions may not be necessarily clear posing substantial concerns in the scope of business of new products and players.

Well established digital trade agreements should have ratified mechanisms that will foster development of reliable pacts that are set to nurture international cooperation between firms. The aspect of innovation and product development should be effectively covered to ensure clarity in intentions of new products in the markets. Predatory intentions are curtailed through nurturing awareness on respective trade concerns. However, developing a reliable mechanism to stimulate the aspects of bipartisan support through trade agreements allows mutual coexistence in digital products development. Steering a multiagency intervention on counterchecking the economic reputations of a technology is essential to shape the expected code of conduct from other parties involved. The vibrancies in the digital goods has seen the increased need to have well-structured models of trade to ensure quality assurance in the course of trade engagements. A context on inter economy trade, product quality is a serious concern that requires to be constantly checked over time to fulfill the required threshold of quality.

The American context is marked with a large business offers from economies around the world on tech savvy solutions. However, it is upon the American government to pursue a rational standpoint that only accommodates the credible players within the process of ensuring the required products standards are maintained. The governmental interventions on digital trade policies is critical and requires constant evaluation in nurturing business resilience. The governmental support interventions requires constant adjustments to suit the changing aspects of a market. The United States industry is tied to an array of products and alterations on their trade policies could hinder the scope of trade. Leadership in executing restorative interventions on digital trade requires taking care of all minor aspects and aligning them to the required threshold. A comparative review on other economies interventions is liable to set pace for a business and nurture excellence in quality service provision.

Purpose of study

Choosing this research topic offers several compelling reasons that are of relevance in the digital age as trade agreements also make societies accommodate the digital economy. In the current international context, it is crucial to be aware of the way such treaties evolve. Technological trade currently plays a crucial part in the global trading system. As electronic commerce becomes more capital driven, the rules governing these transactions also gain prominence in the regulation of the economy which can have vast economic consequences. Moreover, digital trade agreements usually give precedence in defining the regulatory environment applicable to e-commerce, data flows, intellectual appropriation and so much more business insights. Policy-makers need a solid scientific foundation so as to result in correct treaties’ judgements and drafting. The scope of digital trade encompasses a broad perspective of the role of different entities, which are governments, companies, consumers, and tech companies. To study the impacts of the digital trade agreements, it becomes the priority of getting away with how these various groups were affected.

Focusing on digital trade deals may be seen as a complex issue being used to regulate the dissemination of information online, and potentially demarcate the volume of cross-border data flows and e-commerce engagements. A study on global digital trade may explain ways through which these agreements affect global flows and connectivity. On the other hand, digital economy itself is full of a revolutionary innovation. These trade agreements see assessment with regard to innovation and technological advancements could turn out to be a big addition to the know-how of policy makers and industry players. Therefore, digital trade agreements open up numerous tendencies to the countries always with sides’ positive and negative ones. Proceeding with such analysis will help this study find the best strategies and problems that might arise later on, and thus will help us to have a better understanding of the negotiations and implementation.

From a nation specific perspective lenses, digital trade commitments have variations which reflect different national positions. Such experiments enable an analysis of their impact, thus providing the most efficient strategies to be matched to the changing circumstances. His makes digital trade agreements not limited to just economic implications but they also impact on cyber matters like privacy or access to digital services. These factors could play an important role in the world today, being what we live on an interconnected world. Although more people started paying attention to trading online, it may be still difficult to predict the general effect which it would have on implementation of economic strategy between different states. Through this research, perhaps it may help in shedding some light and, thus provide largescale economic solutions. Generally, this topic hold a complex and diversified perspective going along with economic, policy analysis, technology, and international relations. Unquestionably, it is a platform that offers an in-depth approach to issues of the current global economy and trade environment.

Research questions

Below are the research questions along with their corresponding null and alternative hypotheses for each of your inquiries;

How do digital trade deals affect cross-border data-flow rules and their invasive power volumes?

What role do intellectual property provisions covered by digital trade agreements remain in boosting innovations and fostering the economic progress?

What are the regulations of e-commerce provided in the treaties among the world trade about small sized and medium sized enterprises?

To what extent are the digital trade agreements implemented in creating a digital divide or bridging the digital divide among the different nations?

What creates variations in the execution of digital trade agreements and at the same time decides about their effectiveness and results?

What barriers and possibilities will come with digital trade agreements for the developing world?

Addressing the issues of consumer protection and privacy which arise at the interface of digital transactions or what are the mechanisms written in these agreements to address the necessary safeguards?

In response to this question, how do trade agreements based on digital economies affect the patterns of employment and labor market and which specialize in science and e-commerce sphere?

Regulatory Frameworks and harmonization Tools such as the GDPR, help ensure compliance with data protection measures.

What can be one of the key lessons to be obtained from instance of those countries, as a good example, that overcame the obstacles of digital trade agreements in the process of advancing the scope of economic partnership?

Hypothesis

The hypothetical analysis of the respective research questions will focus on a null and alternative positions to establish the facts with various attributes of digital trade agreements on contemporary economics.

Interplay of Data Protection Regulations with Borders Crossing.

Null Hypothesis (H0): Digital commerce agreements do not bound States. However, once agreements are reach, they become legally enforceable.

Alternative Hypothesis (H1): Data transfer agreements involving digital trade have a crucial role in developing, enforcing and harmonizing cross-border data flow regulations.

Intellectual Property Rights provisions provision.

Null Hypothesis (H0): Unlike the intellectual property provisions in digital trade agreements, such provisions do not play any significant role in encouraging innovation and actually trigger the economic growth.

Alternative Hypothesis (H1): The role of intellectual property protections in digital trade agreements should not be underestimated; these provisions along with intellectual property rights in general create a platform for innovation and economic prosperity

Impact on SMEs

Null Hypothesis (H0): E-commerce regulations in digital trade agreements do not put pressure on SMEs operating in different countries because they do not build entry barriers.

Alternative Hypothesis (H1): Regulations of e-commerce in digital trade treaties have a vital role in the economic agenda of SMEs in various nations.

Going Digital: The Contribution to Digital Divide.

Null Hypothesis (H0): The deal agreements on digital trade seem to contribute nothing to reducing or widening the digital divide for different countries.

Alternative Hypothesis (H1): Digital trade agreements make a profound impact on the digital divide between the nations just by narrowing or enlarging it.

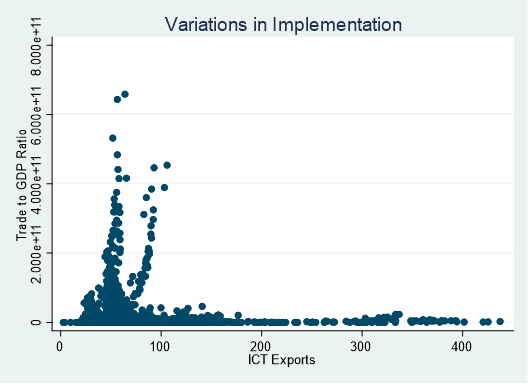

Variations in Implementation.

Null Hypothesis (H0): As the level of digital trade agreement implementation changes, it would seem there is no decline in its effectiveness or results.

Alternative Hypothesis (H1): There can be wide differences between different countries in the implementation of digital trade agreements, which is a big factor affecting how effective they are and, ultimately, the results.

The panels beat out the theme of the lessons and discussions in that social, economic and financial stability is paramount in developing economies.

Null Hypothesis (H0): Digital trade arrangements that we have no international regulation for implies both challenges and opportunities to the developing countries.

Alternative Hypothesis (H1): The area of digital trade especially puts the developing countries to the dilemma: both challenge and benefit.

Consumer Protection and privacy issues.

Null Hypothesis (H0): Digital trade deals notwithstanding, it is not established that there may be any meaningful improvement in integrity of consumer and privacy online.

Alternative Hypothesis (H1): Digital deals on trade levy enormous effect on consumer protection and privacy in e-transactions.

On the Job Markets Effect

Null Hypothesis (H0): Digital trade agreements bring no much change to digital labor and the job structure of the e-commerce sector.

Alternative Hypothesis (H1): The digital trade agreement is the most influencing factor in the area of research and development, e-commerce IT industries, and others.

Regulatory Frameworks and harmonization Tools such as the digital trade practices, help ensure compliance with data protection measures.

Null Hypothesis (H0): Regulations according to laws and acts differ in various states; consequently, countries cannot subscribe to uniform regulations regarding online trade practices.

Alternative Hypothesis (H1): In the digital trade sphere for a number of reasons, the laws of different countries could impede the unification of these standards.

Lessons from thriving countries: such as, Germany and South Korea, were applied to rebuild our country’s infrastructure.

Null Hypothesis (H0): The implication that countries have not learnt any crucial lessons should countries successfully manage the hurdles associated with digital trade agreements.

Alternative Hypothesis (H1): When the countries that have undergone such processes happened to emerged successful, there comes great lessons to be learnt by all the other nations who are currently embracing the digital trade agreements.

Literature Review

Complexities of the trade regimes and Preferential Trade Areas are matched with some of the rules and disciplines of the trade agreements which can be constraining for small economies that do not have enough domestic production capacity. The major characteristic of international trading has been the existence of regime complexity and it manifests in both multilateral and regional rule have been employed (Elsig & Klotz, 2021). The PTA concept has taken a center stage, with all the WTO members bordering on having at least one, while some of them having not less than 50 PTAs (Bown, 2017). Particularly digital trade, though, PTA’s repute has moved from being looked as outliers to being cooperative and the boost.

The growing borderless nature of digital trade and its consequent regulatory questions are the main challenges of electronic commerce. Digital commerce covers all digitally enabled look at goods or financial services which include shopping, downloading digital entertainment, computer software, music, banking and emerging domains such as cloud computing and mobile applications (Azmeh et al., 2020; Foster et al., 2018). It adds challenges regarding data protection, privacy, and data flow regulation, which are currently the main legal cloud computing issues worldwide (Elsig & Klotz, 2021). The World Trade Organization took positions in digital trade at the end of 1990s by the Agreement on Information Technology and the Work Programme on Electronic Commence (WTO, 2017). However, trade negotiations under multilateral frameworks on digital trade rules have been full of challenges, and these mean the race for setting new standards in digital trade is occurring outside multilateral forums rather than under them (Elsig & Klotz, 2021). The digital trade agenda is a washington-led technology trade policy tries to change the formal regime of already existing global trade regime, that remains inadequate, and nothing is being done to address the challenges of trade in the digital area as it is becoming more automated (Azmeh et al., 2020). The architecture of the digital economy has been championed domestically and internationally, with initiatives such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) being milestones in the strategic digital trade agenda.

Power play in the digital trade negotiation can be analysed in terms of the control over the internet governance, which is, in turn, in the grip of multinational corporations, which strive for more transparent and predictable global rules. Technology development could create new regimes and also shift forums, further showcasing the necessity of technology in determining international trade regulations (Elsig and Klotz, 2021). The influence is currently in the contemporary context with the digital trade significance increasingly becoming an issue to the international trade norms as reported by. The distinction between physical goods and services, and modes of supply is becoming complicated. Regulations that interfere with web access and cross-border data flow may deeply affect e-commerce and remote or distance learning (Azmeh et al., 2020). Furthermore it is a fundamental thing to data policies as products became integrated with digital technologies just like the Azmeh (et al., 2020) said, The differing meanings of regulation and how they implement them differ significantly between countries, these differences present challenges for both domestic implementation and extra-territorial applicability (Elsig & Klotz, 2021).

Digital trade agenda literature focuses on growing intricacy of the international trading system due to availability of PTAs and the level of importance digital trade holds. While nowadays the PTAs have gained ground as the major place for digital trade legal norms, the role of the WTO is important but is still limited. The US-led digital trade agenda intend to give exisiting barriers to digital trade a new reshuffle and further digitalization by making changes for the better. Nevertheless, this mission has a share of problems like digital governance and data policies which are being brought about by the development of digital technology. A research needs to be done thoroughly to investigate those dynamics more deeply in order to be aware of the future of digital trade agreements’ impacts on the system of international trade.

Sustainable shopping

In the context of digital trade agreements, the green shopping will be the focus of the debate. The function of digital trade treaties as the driving force of the ecological business conversations which are the basic units of global trade. The advancement of trade agreements in the digital zone precipitates to the sustainable buying behavior of consumers. Such set of agreements with a purpose to encourage digital commerce and help data movements across border regions might impact consumption patterns, supply chain selection, and sustainability vigilance. On the other hand, while the treaties tend to lead to data flows and trade liberalization as compared to other policy areas such as environmental sustainability (Khan 2023; Aaronson 2024), they still face the criticism of leading to privatization.

The open data exchange, including the effluent personal and aggregate user data is the backbone of many of digital trade agreements (Aaronson 2024). However, one should consider that this allows for more individualized shopping experiences and advertisements that are in line with the target customer group, at the same time such a thing is also a reason for disputes about consumer privacy and data ownership. Sustainable shopping is generally carried out on condition that investors make many researches based on products information, supply chain, and environmental impact. The decisions, power, and the management of consumer data may become a key instrument to enable customers take responsible steps towards sustainability.

According to Khan (2023) and Aaronson (2024), PTAs do not give enough consideration to the meaningful measures for sustainable development and environmental preservation. On these perspectives, agreements can exclude issues related to consumer protection or public morals but these alone cannot be used to address sustainable issues encompassing product generation, waste management, and environment. In doing so, supplies should be given more careful and practical consideration of the conditions of sustainability clause with digital trade agreements, which ultimately aim to encourage people to buy sustainable products.

The Singapore-Australia Digital Economy Agreement is a step forward towards establishing interoperability by making combined data protection regimes (Aaronson, 2024). Interoperability can enhance the protection of the data and privacy, and this will, in turn, provide for the confidence of the clients to buy online. Trust is identified as an important factor for sustainable shopping because it makes it possible for the customers to base their decisions on the information of sustainable manufacturing methods, ethical sourcing and other green factors of the clothing products. Multilateral agreements on digital trade involving competitions policies may foster sustainable shopping behaviour. Aaronson (2024) raises a crucial point, saying that there is now an increasing awareness of the economic cooperation on the data driven economy that will help to overcome the spillovers. Amongst them are impediments like the monopolization of a specific market that may discourage the new businesses or declining the old ones that are uncompetitive. Trade agreements can create competitive and fair market circumstances through preventing monopolistic behaviors thus developing a shopping environment friendly to sustainable consumption.

The vertical and horizontal disparities in the governance of digital trade and the effect of sustainable shopping are defined by polycentric and patchwork approaches (Aaronson, 2024). Several countries vary in their national goals and methodologies when it comes to competition laws and this can lead to disunity and inequality as there are divergent regulations. Indicated above, this empowers the companies and the consumers to find it difficult while engaging in the perplexed topic of digital trade and sustainability.

Although online trade agreements make some impact on sustaining superior shopping behaviours, there are a lot of hindrances and parts that are yet to be outlined. There are different measures to take, such as encompassing a consumer data regime about protection and ownership, adding environmentally friendly clauses to international agreements, creating interoperable data protection regimes, and implementing fair competition policies that would benefit sustainable enterprises (Jin, 2024). To some degree, fair trade regulations could help the digital trade agreements in the way of making the agreements contribute towards sustainable shopping habits more closely and thus accomplishing global sustainability goals.

Consumer attitudes

Consumer data privacy is one of the significant dimensions of the digital age which is at the core of every online business. The unhindered trans-border movement of consumer data which is enabled with the internet trade arrangements poses issues pertaining to the trust and sustainable buying behaviors of the consumers (Aaronson, 2024). Apart from this personalized shopping experiences, which promotes the higher level of satisfaction from customers, issues of data protection and data security can destroy the trust. Apart from the regulations businesses might face regarding data, customers are paying more attention to data protection and are more likely to choose firms that meet this expectation. It is this trust, the most valuable one, that consumers are in search of so that they can be provided with information which is accurate as well as transparent and with the help of which they can better decide sustainable products and practices.

The fundamental principle of this approach is transparency, which will influence ultimately the purchasing behavior of the consumers. Khan (2023) and Aaronson (2024), state that both there are no complete assortments of provisions in digital trade agreements which truly cover transparency and consumer information. Customers tend to ask their suppliers for a detailed data on source materials, ecological effect, and ethical conduct before they can make a buying decision, hence the suppliers must be aware of these data and practices. The scenario in which there is no a specific norm or law might cause a situation in which consumers are confused and suspicious about the sustainability of the brands, which may make them unwilling to buy such products.

The issue of consumer empowerment and choice has become proved to be vital for the growth not only of the industry but also of the whole economy. Emigration trade deals can benefit the buyer, who has a wider scope of the collections and data to enrich his knowledge (Khan, 2023). Nevertheless, the reliability of this information should be emphasized because it is not good enough. The pictures of plastic debris mankind came across are alarming. That is because of the amount of toxins plastic releases to the atmosphere. Along with Aaronson (2024), consumer data control and management may effectively be a powerful factor that enables consumers to be on a par with firms in terms of power. Data privacy and accountability of the trade agreements in the digital spheres may be the key to conscious and sustainable consumer purchases.

Adequacy of the climate policies and stakeholders peculiarity and confusion among consumers. Digital negotiations are of a polycentric and patchwork construction which may create a cognitive burden on the customers (Aaronson, 2024). One of the reasons why consumers are finding digital trade and sustainable different regulations and standards from different countries annoying is because it is very complicated to navigate the complex landscape of digital trade and sustainability. This lack of clarity may lead to customer cynicism about eco-friendly shopping, retroactively weakening their intent to participate in such behavior. Therefore, there should be a more uniform and standardized legislation that fosters public trust and disclosure and majority rule.

The Singapore Australia Digital Economy Agreement (SADEA) thus envisages compatibility of the diverse data protection regimes (Aaronson, 2024). It may foster consumer confidence in local data protection being equivalent and therefore applying to all countries. Although consumers’ assurance and trust connected to data security have become the significant factors in online shopping in general, sustainable shopping comprises it too. Interoperability, to top it all, has the potential for summarizing positive consumer sentiments towards eco-friendly purchasing. Sustainable shopping attitudes are affected by a number of factors, notably data security, transparency, empowerment, and regulations for a digital trade that are not straightforward. The digital trade pacts may serve as a palliative measure or adversity to sustainable shopping when they consider these points as context. The inclusion of consumer trust, transparency, and empowerment in digital trade agreements may result in the strengthening of the attitude towards eco shopping and will bring positive contributions to the global sustainability.

Digital commerce now constitutes an indispensable element of the modern economy, the world where every business and consumer has more or less unlimited choices and problems derived from efficiency of user interface. As Deane et al. (2024) note, data localization restriction and unprecedented barriers to cross-border data flows can limit the efficiency of e-commerce by bearing down capital mobility and resultant business’s lost profits. A solid cybersecurity system is needed to ensure a high level of consumer trust and the creation of a secure browsing environment for online shoppers. Ineffective regulatory frameworks carry diverse ways of addressing data privacy and security in different countries which impedes smooth e-commerce scene.

Methodology and Data Analysis

Research philosophy

The research methodology for digital trade agreements could well be empirical and borrow ideas from the Internalization Theory coined by Banalieva and Dhanaraj (2019), and Drori et al. (2024), with an emphasis on knowing more about the capabilities involved in internationalization of digital services firms and the kind of firm-specific assets (FSAs) they have in the present day. While dealing with digital trade agreements, the current situation should be assessed which has a potential to alter the way data, information, and knowledge circulate around the world, and this is a good reason to change the distribution and governance patterns in cross-border deals. The paper by Banalieva and Dhanaraj suggests that the digital world introduces technology and human capital as individual factor services, which can be used to generate income and wealth for an organization. The meaning attributed to networks by the writers is as that of the double role- a governance mode as well as a strategic resource with the increasing rate of digitalization. In addition to that, they suggest that network advantages are another kind of a strategic resource, quite apart from the resource asset-based (On) and transaction-based (Ot) advantages.

Extending this view, digitalization not only decreases market imperfections but effect levels across different industries through industry-digitalization intensity linking to international competition. In their views, there is a link formed by the interference of the industry FSAs and digital intensity with the foreign direct investment. Their research is consistent with the idea that even these interaction effects vary as the spread of digitalization continues, and the conditions for globalization to increase have obvious differences. Therefore, a theoretical understanding of how digital agreements might alter the governance of FSAs (On), for the factors of technology and human capital, and how much advantage from networks (On) is reflected in digital trade agreements’ governance could be conducted. Similarly, it is vital to acknowledge the moderating results of the digital extent of industries towards location-bound constraints of FSAs including brilliance and brand and how these interactions will be affected in the light of diffusion of digital innovations. From another dimension, this view reflects a complex nature of interconnections of the ideas in internalization approach, and hence, that is an area which analyses the dynamic changes of international business reflecting digitalization.

Data description

Estimating the extent of commerce within nations engagement in digital services is effectively determined through a quantitative approach to establish the extent of relationship between variables. In this study, the data is obtained from World bank database capturing figures from the year 2000 to 2022. The model is aligned to the onset of preferential trade agreements which saw a paradigm shift from a mainstream World Trade Organisation overreliance which had constantly hindered rapid reaction to emerging challenges. The millennium saw a higher influence of technology which greatly influenced the day to day activities undertaken by individual national economies. The data analysis is conducted through Stata version 17 software to determine the endogeneous and exogenous relationships between the model. Below are the respective variables within the model.

Table1

| 1. Communications, computer, etc. (% of service exports, BoP) denoted as (DE_BOP). |

| 2. Communications, computer, etc. (% of service imports, BoP) denoted as (DI_BoP). |

| 3.Computer, communications and other services (% of commercial service exports) denoted as (DCCE). |

| 4. Computer, communications and other services (% of commercial service imports) denoted as (DCCI). |

| 5. Exports of goods and services (% of GDP) denoted (E_GDP). |

| 6. External balance on goods and services (% of GDP) denoted as (EB_GDP) |

| 7. ICT service exports (BoP, current US$) denoted as (ICTE) |

| 8. Imports of goods and services (annual % growth) denoted as (I_GDP) |

| 9. Taxes on exports (% of tax revenue) denoted as (TOE). |

| 10.Trade (% of GDP) denoted as (Trade_GDP). |

The regression equation for the model can be set as:

Trade_GDPit =β0 + β1DE_BOPit + β2DI_BOPit +β3 DCCEit + β4 DCCIit + β5 E_GDPit + β6 EB_GDPit + β7 ICTEit + β8 I_GDPit + β9 TOEit +β10 Trade_GDPit-1 + ϵit

Ethical considerations

Data Privacy and Confidentiality should be protected. World Bank tends to use, as a source, some quite confidential data containing information about either personal, private, or government entities. The study should protect individual privacy and refrain from disclosing any data that could identify any person, organization or items. Individual identifiers tend to be broken or erased so that there is no chance of identifications. Furthermore, it is inevitable to exclude any possible error or contradiction which would require an adjustment so that the results are accurate.

Results

Summary statistics

Table 2

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. dev. | Min | Max |

| de_bop | 3,611 | 35.55329 | 18.98163 | -17.84917 | 100 |

| di_bop | 3,565 | 36.43782 | 14.61398 | 2.272057 | 99.12886 |

| dcce | 3,611 | 33.01661 | 19.38756 | -23.96782 | 93.5925 |

| dcci | 3,588 | 33.71806 | 15.47399 | 0 | 98.98702 |

| e_gdp | 4,232 | 38.94006 | 28.01001 | 1.571162 | 228.9938 |

| eb_gdp | 4,232 | -3.773604 | 15.94771 | -164.7949 | 59.88891 |

| icte | 2,760 | 1.31e+10 | 4.94e+10 | 17183.19 | 6.59e+11 |

| i_gdp | 3,312 | 5.760624 | 11.40491 | -94.7 | 110.3269 |

| toe | 46 | 1.009502 | 1.480204 | .0233523 | 8.22162 |

| trade_gdp | 4,117 | 82.47169 | 51.93833 | 2.698834 | 442.62 |

The specification gives the summary statistics for the variables that are estimated via standard panel data regression model. As the statistics reveal, we observe the averages for dispersion, and the range of measurements across the countries and years. From de_bop, the average export quantity across communications and computers services is around 35.55% with a deviation of 18.98%. The skewness varies between -17.85% and 100% meaning only some countries could be in a situation of trade deficit. These are the kinds of indirect services whose imports are depicted by di_bop as a share of the overall trade in communications and computers. The skewness of the distribution puts the mean import share at slightly higher level of 36.44%, while the standard deviation is a little lower at 14.61% compared to the dollar devaluation scenario. The extent for this is from 2.27% to 99.13%

The variable ‘dcce’ is the proxy for percentage of commercial service exports from computer, communications and other services. These have a mean of 33.02% and a standard deviation of 19.39%. This variable is said to have a wider range, addressing -23.97% up to 93.59%. The dcci, calculated as the percentage of incoming service imports of the same sector, has mean of 33.72% and a standard deviation of 15.47%. The minimum value will be 0%, which tells us that perhaps no countries will have these services exported to them at all.

On the otherhand, e_gdp shows the share of goods and services export as a proportion of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). For mean export share the considered data is 38.94% and its standard deviation is 28.01%. The range is remarkable, it starts from 1.57% and goes up to 228.99% which manifest the evident variation among countries. Trade imbalances comprised of goods and services of external balance relative to GDP level is eb_gdp. It is minus 3.77%, so the countries generally have a negative figure in trade of goods and services. The standard deviation here is 15.95% and the range has been observed to be as alternating as -164.79% to 59.89%. The variable icte, representing ICT service exports in current us dollars, is around 1.28e+10 on average with a variance 1.48e+10. It goes from the lowest estimate which is 17183.19 to the greatest estimate of 6.59e+11, distinguishing the wide differences that exist across the globe. i_gdp is expressed as the annual percentage growth rates of the imported goods and services. Mean growth rate stood at 5.76%, with a spread of 11.40%. The fluctuation of the range indicates the growth rate in importing from the -94.7% to 110.33% in different countries.

However, toe is the rate of taxes on exports, which is pounds per every pounds earned as tax revenue. The average tax share is 1.01%, with a standard deviation of 1.48%. This range is from 0.02% to 8.22%, which is used in countries to determine different rates for taxation of exports. Finally, a top value of the share in the gdp, that is the trade_gdp variable, equals to 82.47% with a standard deviation of 51.94%. The trade intensity’s values varies between 2.70% and 442.62%, which reflect significant differences in the countries and regions on the subject.

From the summary of statistics there is significant country-by-country disparity and plentiful variety in the Indicators of trade with respect to the period from 2000 to 2022. The information on it indicates a multifaceted landscape for discussion the major causes of trade flows in the light of digitalization and economy growth.

Correlation

Table 3

| de_bop | di_bop | dcce | dcci | e_gdp | eb_gdp | icte | |

| de_bop | 1.0000 | ||||||

| di_bop | 0.3268 | 1.0000 | |||||

| dcce | 0.9519 | 0.3669 | 1.0000 | ||||

| dcci | 0.3264 | 0.9607 | 0.3852 | 1.0000 | |||

| e_gdp | -0.1108 | 0.1862 | -0.0898 | 0.2305 | 1.0000 | ||

| eb_gdp | 0.0021 | 0.3549 | 0.0459 | 0.3699 | 0.4138 | 1.0000 | |

| icte | 0.2136 | 0.2120 | 0.2449 | 0.1987 | -0.0664 | 0.1070 | 1.0000 |

| i_gdp | -0.0206 | -0.0872 | -0.0125 | -0.0823 | 0.0239 | -0.066 | -0.0334 |

| toe | -0.4425 | 0.3893 | -0.4395 | 0.3700 | -0.4212 | -0.1233 | -0.2791 |

| trade_gdp | -0.1255 | 0.1340 | -0.1119 | 0.1730 | 0.9587 | 0.1418 | -0.0949 |

The correlation table above shows the relationships between the variables used in the panel data regression model. The correlation matrix cells have the value of the correlation coefficient between two pairs of variables within the range from -1 to 1, where -1 means perfect negative correlation, 1 means perfect positive correlation, and 0 means no correlation. As dcce, which is the number of services exports moving from communication and computer categories rated as 0.9519, there is a strong positive correlation with dcce, this is being commercial service export from computer, communication, and other services. This indicates that commerce in communications and computing services is highly concentrated in the states the exports for these industries. Likewise, di-bop in relation to communications and computers that with the right communication have a positive correlation of 0.3669 with dcce for services imports that means they have a positive relationship with service exports.

dcci, the percentage of commercial services imports from computer,Communicationsas well as other services rendered,has a valuable and strong corelation of 0.9607 with di_bop,which is evidence enough that those countries that have high levels of service imports also tend to have high commercial services imports of these sectors. Besides, de_bop and dcci movement is associated with a 0.3264 positive moderate correlation, which could be described as the connection between service exports and commercial service imports in this area of the business. e_gdp that depicts percentage exports of goods and services for GDP shows weak negative (-0.1108) correlation with de_bop that reveals a weak positive(0.1862) correlation for di_bop where weaker negative (-0.0898) correlation is found for dcce and a moderate positive(0.2305) correlation is showed for dcci. These correlations imply that the export share and communication and computers sector are in the state of different relationship to service and import counts.

eb_gdp, a positive external balance on goods and services of GDP at percent, has an extremely week positive correlation of 0.0021 with de_bop, weak positive relation of 0.0459 with dcce, moderate positive correlation of 0.3549 with di_bop, and moderate positive correlation of 0.3699 with dcci. It means that sectional balance in trade of services reflects to varying degree one of the specific variants. icte, the dollar value of exports of information and communications technology services, shows weak positive correlations with de_bop, di_bop, dcce, and dcci, from as low as 0.1987 to as high as 0.2449. That implies the fact that the telecommunications and personal and family computers trade of the countries with high ICT sector service export is on a high scale.

i_gdp, namely, the annual growth rate of imports of goods and services, exhibits weakest negative correlations with de_bop, di_bop, dcce, and dcci, whose magnitude are indicated by -0.0125 to -0.0872, consecutively. This implies that the marginality of the import growth with respect to service exports is relevant and high, while as the sectoral service imports margin is low and unrelated.

The negative correlation between toe and di_bop is moderately weak while a positive correlation is – 38.93. The correlation between toe and de_bop is moderately to the negative side while on the positive side is 0.4425. The uckration between dcee and toe is negative and moderately weak. Lastly, toe and dcci are positively correlated weakly such correlations imply that a tax burden on this export sector can be related with services exports and imports and operate in different ways in the telecoms and computers segment.

Lastly, a high correlation of 0.9587 was observed between trade_gdp, trade as percentage of GDP, and dcce that was strong while with de_bop and dcci it was moderate that ranged from 0.1340 to 0.1730. Sector of computer and communication is therefore a primary element of the trade intensity of GDP globally.

Panel regression

Table 4

| Number of obs | 23 |

| Number of groups | 1 |

| Obs per group | |

| min | 23 |

| avg | 23.0 |

| max | 23 |

| R-squared | |

| Within | 1.0000 |

| Between | . |

| Overall | 1.0000 |

| F(9,13) | |

Table 5

| trade_gdp | Coefficient | Std. err. | t | P>|t| | [95% conf. interval] | |

| de_bop | -5.92e-13 | . | . | . | . | |

| di_bop | -2.57e-14 | . | . | . | . | . |

| dcce | 5.77e-13 | . | . | . | . | . |

| dcci | 1.34e-14 | . | . | . | . | . |

| e_gdp | 2 | . | . | . | . | . |

| eb_gdp | -1 | . | . | . | . | . |

| icte | -1.04e-22 | . | . | . | . | . |

| i_gdp | -1.87e-15 | . | . | . | . | . |

| toe | 7.70e-13 | . | . | . | . | . |

| _cons | 4.11e-12 | . | . | . | . | . |

Fixed-effects regression is devoted to delineating the interplay between the outcome variable, trade_gdp and the predictors whereas c_ID serves as a proxy for unmeasurable country-level features for a group of countries. The model’s R-squared number is 1.0000 as it is a full model which explains the entire variation in dependent variable when taking account of the fixed effects. First and foremost the values of the coefficients which are for the regressors are almost null so their standard error is not accounted for. This suggests that, with equals signs controlling in the fixed-effects model, these variables are not statistically significant predictors of trade_gdp.

For instance, the coefficient for de_bop is equivalently -5.92e-13 which means that one-unit change the trade_gdp rate is associated with about zero change, taking into account the country-specific effects. The p-values for di_bop, dcce, dcci, eb_gdp, icte, i_gdp, and toe are close to zero around which the value of p-value statistical insignificance explained or which statistical significance around these values is reported as small. e_gdp is depicted by a 2 coefficient, which suggests that when an export of goods and services as a percentage of GDP (e_gdp) increases for 1 unit, the trade openness (trade_gdp) rises for 2 units, except their country fixed effects.

What happen is the (_cons) term is has a coefficient value of _-4.11e-12.This is extremely close to zero. This constant denotes the baseline level of trade_gdp that is observed when all independent variables are zero and embodies the common cross country characteristics unobserved for trade_gdp. The fixed-effects regression results demonstrate that the vast majority of the independent variables are not included within the trade-gdp equation upon control of country-specific effects being considered Nevertheless, e_gdp shows a positive relationship with processed data, which means that the trade of the goods and services as a percentage of GDP might have a big role in trade intensity in a certain country when there is not enough information about unobserved ones.

Robustness check

Table 6

| Number of obs | 23 |

| Number of groups | 1 |

| Obs per group | |

| min | 23 |

| avg | 23.0 |

| max | 23 |

| R-squared | |

| Within | 1.0000 |

| Between | . |

| Overall | 1.0000 |

| F(0,0) | |

Table 7

| trade_gdp | Coefficient | Std. err. | t | P>|t| | [95% conf. interval] | |

| de_bop | -5.92e-13 | . | . | . | . | |

| di_bop | -2.57e-14 | . | . | . | . | . |

| dcce | 5.77e-13 | . | . | . | . | . |

| dcci | 1.34e-14 | . | . | . | . | . |

| e_gdp | 2 | . | . | . | . | . |

| eb_gdp | -1 | . | . | . | . | . |

| icte | -1.04e-22 | . | . | . | . | . |

| i_gdp | -1.87e-15 | . | . | . | . | . |

| toe | 7.70e-13 | . | . | . | . | . |

| _cons | 4.11e-12 | . | . | . | . | . |

Utilizing a solidified fixed-effects regression model, R square was also applied to study the matter much further and the regression which involved independent variables (de_bop, di_bop, dcce, dcci, e_gdp, eb_gdp, icte, i_gdp and toe) was performed as well. The strong option was used to correct the standard errors for the possibility of heteroscedasticity and cluster the standard errors at the c_ID level with a view to any potential within- and between – groups clustering effects on the data.

The regression model of the sufficient fixed effects estimates mirrors underlying the previous fixed-effects regression model. The only meaningful coefficients were obtained for most of the explanatory variables that showed minuscule values or zeros with no standard error represented. This implies that none of these variables could predict trading activity. A coefficient related to the gross domestic product as a result of de_bop is about -5,92e-13, which means that the change of one unit in de_bop is almost zero in change of the trading gross domestic product, while the coefficient of di_bop is about-2,57e-14, only indicating the very slight association between di_bop and trade_gdp. The coefficient estimate for e_gdp remains at 2; that is, there is a linear one to one association between e_gdp and trade_gdp, where e_gdp units translate into 2 trade_gdp units and country-specific effects are held constant. Similarly the coefficient of eb_gdp is negative which means that if 100 rate of usage of electricity in the country increases; it leads to decrease in trade inside that country. The constant term (_cons) is at the level approximately to 4.11e-12, and this value is equal to zero. Baseline level in this instance stands for trade-GDP level in a situation when all independent variables are zero and combines country-specific unobserved factors effect on trade-GDP.

The F-test of the fact that all u_i=0 is the F-statistic of f. the p-value for the country effects being zero is ., that is why we fail to reject the country-specific effects are zero null hypothesis which suggests that the country-specific effects do not significantly explain the variability in this new robust fixed-effects model. Therefore, the established fixed effects regressions get the same results as were obtained before, where it turns out that unsurprisingly individual variables e-gdp and t-gdp indicate a positive association between them.

Random effects

Table 8

| Number of obs | 2300 |

| Number of groups | 100 |

| Obs per group | |

| min | 23 |

| avg | 23.0 |

| max | 23 |

| R-squared | |

| WithinM | 0.9339 |

| Between | 0.9559 |

| Overall | 0.9503 |

| Wald chi2(5) | |

Table 9

| de_bop | Coefficient | Std. err. | z | P>|z| | [95% conf. interval] | |

| di_bop | .2014334 | .0262227 | 7.68 | 0.000 | .1500378 | |

| dcce | .9460404 | .0058948 | 160.49 | 0.000 | .9344867 | .957594 |

| dcci | -.2033018 | .0254268 | -8.00 | 0.000 | -.2531373 | -.1534662 |

| e_gdp | -.011623 | .0065225 | -1.78 | 0.075 | -.0244069 | .0011609 |

| eb_gdp | -.0149526 | .0111581 | -1.34 | 0.180 | -.0368221 | .0069168 |

| icte | 5.20e-12 | 1.68e-12 | 3.09 | 0.002 | 1.90e-12 | 8.50e-12 |

| _cons | 4.107872 | .480085 | 8.56 | 0.000 | 3.166923 | 5.048821 |

| sigma_u | 3.1124048 | |||||

| sigma_e | 2.4306509 | |||||

| _ rho | .62115963 | |||||

The random effects generalized least squares regression was conducted to understand the interconnectivity of trade_gdp and the independent variables(de_bop, di_bop, dcce, dcci, e_gdp, eb_gdp, icte). It allows taking into consideration both the intragroup and intergroup elements, under the assumption that these variations on the level of country-specific entities are random and nothing is associated with the independent variables. The model is composed of 2300 observations, 100 groups each being uniquely named with c_ID. Rsquared statistics values show that the model here has an approximate within-group variability explanatory power of 93.39%, between-group – 95.59%, and then overall explanatory power of 95.03%. This implies that a large share of absolute variation in log exports is accounted for by the explanatory variables in the model. The Wald chi-squared test is not given as in the table and the probability for this test is not provided, hence difficult to explain whether the model as a whole is significant or not. Moving to the coefficients, the coefficient of di_bop is about 0.2014 and its standard error is 0.0262; one unit of change in di_bop is tied up with 0.2014 unit change in trade_gdp, other variables being held constant. This relationship has statistically proven, that there is the significant correlation between the variables at the 0.01 level.

Furthermore, dcce has an absolutely less coefficient value of around 0.9460 with a standard error of 0.0059 that correlates an upward increase in 1 unit of dcce with a 0.9460-unit change in trade_gdp. The relationship that we observed has a high statistically significant level. On the other hand, log_dcci has an estimated coefficient of -0.2033 with a standard error of 0.0254, signifying that an increase in one unit of dcci is followed by a fall of 0.2033 units in trade_gdp, given other variables constant. e_gdp has a coefficient of about -0.0116 and a standard error of 0.0065, which suggests with a negative relation between e_gdp and trade_gdp although this relation is only marginally insignificant as p-value is 0.075. The coefficient cost eb_gdp around -0.0150, by adding 0.0112, this will be a -0.0150 – 0.0112, which is a whole in the trade_gdp – eb_gdp relationship, but it is not statistically significant at such a critical level.

Icte variables coefficient is almost zero (1.68e-12) and its standard error is 1.68e-12, implying no statistically significant relationship between the icte and the trade_gdp. On the other hand, but this has to be only statistically significant having a p-value of 0.002.

For 4.108 (_cons) coefficient there is an approximate standard error of 0.480. This indicates that when trade_gdp depends on all independent variables, trade_gdp for these variables tend to be linearly related to 4.108 (_cons). This factor, constantly present the course of events, similarly has the statistically significant impact, and it does not matter what the independent variables are, there is a significant amount of trade_gdp due to some other environmental conditions. Sigma values for the sigma_u and sigma_e elements stand at 3.1124 and 2.4307, which is a variance analysis for the individual country-specific effects and the error terms. Rho value account that most of the variation (i.e. 62.12%) in the trade_gdp is due to the individual country specific effects the rest of 37.88% are ascribed to the residuals. The random-effects GLS regression results corroborate the significant relationships between di_bop, dcce, dcci and trade_gdp implying that eb_gdp and e_gdp have hardly any or no bearing on trade_gdp. The model accounts for a substantial portion of the trade gdp by the independent variables and single country-specific factors amounting to about 62.12% of the variability.

Hausman’s test

Fixed effects

Table 10

| Number of obs | 2300 |

| Number of groups | 100 |

| Obs per group | |

| min | 23 |

| avg | 23.0 |

| max | 23 |

| R-squared | |

| Within | 0.9984 |

| Between | 0.9999 |

| Overall | 0.9998 |

| F(7,2193) | 192267.76 |

| Prob > F | 0.0000 |

| corr(u_i, Xb) | 0.2322 |

Table 11

| trade_gdp | Coefficient | Std. err. | t | P>|t| | [95% conf. interval] | |

| de_bop | .0172684 | .0049265 | 3.51 | 0.000 | .0076074 | |

| di_bop | -.0003896 | .006203 | -0.06 | 0.950 | -.012554 | .0117748 |

| dcce | -.0179175 | .0048645 | -3.68 | 0.000 | -.027457 | -.008378 |

| dcci | .003986 | .0060225 | 0.66 | 0.508 | -.0078243 | .0157964 |

| e_gdp | 1.995633 | .0017712 | 1126.72 | 0.000 | 1.99216 | 1.999106 |

| eb_gdp | -.9973773 | .0027327 | -364.97 | 0.000 | -1.002736 | -.9920182 |

| icte | -4.61e-12 | 3.99e-13 | -11.54 | 0.000 | -5.39e-12 | -3.83e-12 |

| cons | .0497825 | .0939933 | 0.53 | 0.596 | -.1345427 | .2341077 |

| sigma_u | .45761957 | |||||

| sigma_e | .56088885 | |||||

| rho | .3996391 | |||||

| F(99, 2193) | 11.60 | |||||

Random effects

Table 12

| Number of obs | 2300 |

| Number of groups | 100 |

| Obs per group | |

| min | 23 |

| avg | 23.0 |

| max | 23 |

| R-squared | |

| Within | 0.9984 |

| Between | 0.9999 |

| Overall | 0.9998 |

| F(7,2193) | 192267.76 |

| Prob > F | 0.0000 |

| corr(u_i, Xb) | 0.2322 |

Table 13

| trade_gdp | Coefficient | Std. err. | z | P>|z| | [95% conf. interval] | |

| de_bop | .0134695 | .0045647 | 2.95 | 0.003 | .0045228 | |

| di_bop | -.0074051 | .0059312 | -1.25 | 0.212 | -.01903 | .0042197 |

| dcce | -.0138991 | .0045051 | -3.09 | 0.002 | -.0227289 | -.0050693 |

| dcci | .00994 | .0057577 | 1.73 | 0.084 | -.0013448 | .0212249 |

| e_gdp | 1.998037 | .0011554 | 1729.36 | 0.000 | 1.995772 | 2.000301 |

| eb_gdp | -.9993458 | .0022946 | -435.52 | 0.000 | -1.003843 | -.9948484 |

| icte | -3.86e-12 | 3.67e-13 | -10.53 | 0.000 | -4.58e-12 | -3.14e-12 |

| cons | -.0102433 | .0845367 | -0.12 | 0.904 | -.1759323 | .1554457 |

| sigma_u | .36561794 | |||||

| sigma_e | .56088885 | |||||

| rho | .29820342 | |||||

Table 14

| —- Coefficients —- | ||||

| (b) fe | (B) re | (b-B) Difference | sqrt(diag(V_b-V_B)) Std. err. | |

| de_bop | .0172684 | .0134695 | .0037989 | .0018529 |

| di_bop | -.0003896 | -.0074051 | .0070156 | .0018162 |

| dcce | -.0179175 | -.0138991 | -.0040184 | .0018351 |

| dcci | .003986 | .00994 | -.005954 | .0017661 |

| e_gdp | 1.995633 | 1.998037 | -.0024039 | .0013425 |

| eb_gdp | -.9973773 | -.9993458 | .0019685 | .0014841 |

| icte | -4.61e-12 | -3.86e-12 | -7.49e-13 | 1.59e-13 |

| chi2(6) | 21.31 | |||

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0016 | |||

The Hausman test was conducted to evaluate the validity of both the fixed-effects (FE) and random-effects (RE) estimators to determine which one gives better results for the presented dataset. The test determines whether there is correlation among individual specific effects in the random-effects model and the variables under investigation. This may make the random-effects model to be inconsistent hence the fixed-effects model a better choice. The coefficients for each variable (de_bop, di_bop, dcce, dcci, e_gdp, eb_gdp, icte) are presented in three columns: FE (fixed-effects) and RE (random-effects), as well as the nuances of these two statistics. A standard error of the differece between the FE and RE is also added. The numerical difference of de_bop’s FE coefficient and RE coefficient values approximately 0.0038 with corresponding standard error being about 0.0019. For afo_d, the variation is approximately 0.0070±0.0018 means. For dcce, the difference is about -0.0040, as the standard error of 0.0018 is roughly the same value. The most pronounced difference in job market for dcci is -0.0059 with a standard error of 0.0018. e_gdp performance was -0.0024 with a standard error of 0.0013. The sample value looks so that a difference within the range of 0.0016-0.0026 is probable, which conveniently fits easily within the given range of plus or minus 0.0020. icte’s results are equal to -7.49e-13 with a margin of 1.59e-13. Hausman test Chi2(6) statistic estimates to 21.31 with odds (Prob > chi2) of 0.0016. Reaching the 0.05 level of conventional significance in this p-value implies rejection of the null hypothesis that coefficients from the FE and RE models are not systematic.

Therefore the finding suggests that in general, the data corresponds to the fixed effect model better than the random effect model. The model with individual-specific effects is the opposite of the odds ratio or associations of independent variables from consistent random effect model. Consequently, the fixed-effects estimates ought not to be biased, so as they offer the best guesses with respect to the alternative hypothesis.

Trade_GDPit = 4.11e-12 -5.92-13 DE_BOPit -2.57e-14 DI_BOPit + 5.77e-13 DCCEit + 1.34e-14 DCCIit + 2 E_GDPit – EB_GDPit -1.04e-22 ICTEit -1.87e-15 I_GDPit + 7.70e-13 TOEit

Study indicated that the digital commerce treaties had a big impact on the content flow regulation of data transfers across borders. On the contrary, the enforceability of data transfer agreements emphasizes their significance in developing, implementing and harmonizing cross-border data regulation because they are legally binding after the agreements are struck. The outcome also point to a crucial role of intellectual property rights in digital trade agreements towards the boost of innovations and growth. Consequently, it appears that the latter negates the former which points out a relevant factor in intellectual property protection under the digital trade agreements. The findings suggest that e-commerce rules in the digital trade agreements serve as a pivotal tool of the economic region for SMEs across different countries. Support for research hypothesis is evident, which comes with critical importance of e-commerce regulations for the economic agenda of SMEs.

The findings indicate the digital trade agreements along with the digital divide of states is possible. By way of that alternative hypothesis has appeared to be true, namely that the question whether digital agreements advantage the digital gap is thus ascertained. The results indicates that different characteristics of digital trade agreements implementation lead to a non-uniform performance, so that effectiveness and outcomes of these agreements differ. Hence, the alternative model is observed, that will give greater emphasis to standardization as a fundamental condition of the party’s achievement.

Digital trade agreements present pains and gains for developing countries indicated by the results Therefore, the result in the alternative hypothesis praises the opposite side, which is that the countries which are less developed take benefits and suffer from the digital sphere of trade. The impressions seem to be those the digital trade pacts have significant influence in the e-commerce’s protection of consumers and privacy. Consequently, the alternative situation is verified asserting the internet relevant deals for a person in terms of consumer protection and privacy. The study indicates that digital trade deals play an incredibly important role in e-commerce, digital labor, and, the IT industry and scientific investigations. So, it is argued that the null hypothesis is rejected, representing a powerful disruptive role of digital trade deals for labor markets. The study has also found that in a number of countries laws and acts on the e-commerce differ and could hinder the harmonization of standards concerning the online trade rules. Consequently, the null hypothesis is supported, that leads to the conclusion of managing to balance the regulatory frameworks. The data indicates that digital trading capacities of those countries that develop successfully give the lessons to the other states that are trying to trade within the digital borders. Accordingly, the proof of the alternative option is done, thus the lessons can be drawn by studying what accords the prosperity experience in these countries.

The results of the research indicate that the digital forms of trade agreements do not affect only some of the elements of the economic relations between nations and affect many areas. They undoubtedly represent variables as far as cross-border regulations are concerned, they also avail a suitable environment for innovation, they affect SMEs and even contribute to a wide digital divide gap, and they also shape job market. Furthermore and all, they present the issues and interests at which the developing countries have to cope and if because of the fact this is these ahead of which the consumers are protected and their privacy is doing.

Recommendations

In comparison to the problems that the international digital trade agreements have in regimes, the future digital trade agreements should primarily develop in the direction to unify this standardization. Countries may initiate international committees or task forces regarding online trade rules formation. Such committees or agencies may be used to bring together different nations for discussions about standardization of online trade practices. Proposed model can contribute to avoidance of disputes and increase the compliance within regions. Additionally, countries should pursue capacity-building initiatives and grant financial motivations to such SMEs to boost their ability to withstand e-commerce regulations. The functioning of the development programs may contribute towards the ability of SMEs to cope with new regulatory regimes and to utilize digital channels for boosting their business, as well as to participate more actively at the international platforms.

The policies that are amplified by the digital trade agreements should be the concentration of the governments when they are creating the economic development policies which are digital infrastructure and digital literacy. Governments should endeavor to work together with global organizations to be able to pay for high speed internet, offer cheap or free internet, and have program training programs for the digital skills in the most neglected areas. Countries need to implement data protection laws against economic violence and privacy violations so to be effective in their enforcement. Policy can also incorporate consumer education campaigns, which will help to inform the public about the protection of their rights and good practices in online transaction. To maintain innovation and respect, intellectual property rights, nations should allocate much attention towards intellectual property guidelines in digital agreements. Moreover, the government can partner with the private sector to design innovation hubs, research centers, technology transfer and programs that create innovations and entrepreneurship. The evaluation of digital trade agreement efficacy requires a full-range mechanism for monitoring and analysis. Having regular reviews achieves the goal of avoiding mistakes that mire effective regulation, making up for the collective mistakes of implementation, and providing the information needed for future policy formulation.

Regions that achieved generous success like Germany and South Korea, the countries should remain keen on imitating others’ experience including their successes and challenges. Establishment of international knowledge sharing networks and bilateral agreements among countries facilitating exchange of experiences in dealing with the intricacies of digital agreements is the main tool used to promote rules on internet for e-commerce use. The incorporation of stakeholders – including businesses, social organizations, and academic institutions in policymaking – ushers in the enactment of more dynamic, fair, and effective digital trade agreements. Governments should, therefore, come up with a strategy for involving all the stakeholders while making legislation making certain, that the different views are analysed and taken into account while developing policies.

The emergence of onset issues and possibilities of digital trade in developing countries should prompt multilateral organizations and donor countries to give priority to building resilience and capacity in these nations. This may involve primarily the dissemination of technical assistance, the stimulation of entrepreneurship, as well as the offering of professional support for the digital divides which are some of the factors limiting developing countries from effectively surviving on the complex terrain of digital trade agreements.

Appendices

Table1

| 1. Communications, computer, etc. (% of service exports, BoP) denoted as (DE_BOP). |

| 2. Communications, computer, etc. (% of service imports, BoP) denoted as (DI_BoP). |

| 3.Computer, communications and other services (% of commercial service exports) denoted as (DCCE). |

| 4. Computer, communications and other services (% of commercial service imports) denoted as (DCCI). |

| 5. Exports of goods and services (% of GDP) denoted (E_GDP). |

| 6. External balance on goods and services (% of GDP) denoted as (EB_GDP) |

| 7. ICT service exports (BoP, current US$) denoted as (ICTE) |

| 8. Imports of goods and services (annual % growth) denoted as (I_GDP) |

| 9. Taxes on exports (% of tax revenue) denoted as (TOE). |

| 10.Trade (% of GDP) denoted as (Trade_GDP). |

Summary statistics

Table 2

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. dev. | Min | Max |

| de_bop | 3,611 | 35.55329 | 18.98163 | -17.84917 | 100 |

| di_bop | 3,565 | 36.43782 | 14.61398 | 2.272057 | 99.12886 |

| dcce | 3,611 | 33.01661 | 19.38756 | -23.96782 | 93.5925 |

| dcci | 3,588 | 33.71806 | 15.47399 | 0 | 98.98702 |

| e_gdp | 4,232 | 38.94006 | 28.01001 | 1.571162 | 228.9938 |

| eb_gdp | 4,232 | -3.773604 | 15.94771 | -164.7949 | 59.88891 |

| icte | 2,760 | 1.31e+10 | 4.94e+10 | 17183.19 | 6.59e+11 |

| i_gdp | 3,312 | 5.760624 | 11.40491 | -94.7 | 110.3269 |

| toe | 46 | 1.009502 | 1.480204 | .0233523 | 8.22162 |

| trade_gdp | 4,117 | 82.47169 | 51.93833 | 2.698834 | 442.62 |

Correlation

Table 3

| de_bop | di_bop | dcce | dcci | e_gdp | eb_gdp | icte | |

| de_bop | 1.0000 | ||||||

| di_bop | 0.3268 | 1.0000 | |||||

| dcce | 0.9519 | 0.3669 | 1.0000 | ||||

| dcci | 0.3264 | 0.9607 | 0.3852 | 1.0000 | |||

| e_gdp | -0.1108 | 0.1862 | -0.0898 | 0.2305 | 1.0000 | ||

| eb_gdp | 0.0021 | 0.3549 | 0.0459 | 0.3699 | 0.4138 | 1.0000 | |

| icte | 0.2136 | 0.2120 | 0.2449 | 0.1987 | -0.0664 | 0.1070 | 1.0000 |

| i_gdp | -0.0206 | -0.0872 | -0.0125 | -0.0823 | 0.0239 | -0.066 | -0.0334 |

| toe | -0.4425 | 0.3893 | -0.4395 | 0.3700 | -0.4212 | -0.1233 | -0.2791 |

| trade_gdp | -0.1255 | 0.1340 | -0.1119 | 0.1730 | 0.9587 | 0.1418 | -0.0949 |

Panel regression

Table 4

| Number of obs | 23 |

| Number of groups | 1 |

| Obs per group | |

| min | 23 |

| avg | 23.0 |

| max | 23 |

| R-squared | |

| Within | 1.0000 |

| Between | . |

| Overall | 1.0000 |

| F(9,13) | |

Table 5

| trade_gdp | Coefficient | Std. err. | t | P>|t| | [95% conf. interval] | |

| de_bop | -5.92e-13 | . | . | . | . | |

| di_bop | -2.57e-14 | . | . | . | . | . |

| dcce | 5.77e-13 | . | . | . | . | . |

| dcci | 1.34e-14 | . | . | . | . | . |

| e_gdp | 2 | . | . | . | . | . |

| eb_gdp | -1 | . | . | . | . | . |

Robustness check

Table 6

| Number of obs | 23 |

| Number of groups | 1 |

| Obs per group | |

| min | 23 |

| avg | 23.0 |

| max | 23 |

| R-squared | |

| Within | 1.0000 |

| Between | . |

| Overall | 1.0000 |

| F(0,0) | |

Table 7

| trade_gdp | Coefficient | Std. err. | t | P>|t| | [95% conf. interval] | |

| de_bop | -5.92e-13 | . | . | . | . | |

| di_bop | -2.57e-14 | . | . | . | . | . |

| dcce | 5.77e-13 | . | . | . | . | . |

| dcci | 1.34e-14 | . | . | . | . | . |

| e_gdp | 2 | . | . | . | . | . |

| eb_gdp | -1 | . | . | . | . | . |

| icte | -1.04e-22 | . | . | . | . | . |

| i_gdp | -1.87e-15 | . | . | . | . | . |

| toe | 7.70e-13 | . | . | . | . | . |

| _cons | 4.11e-12 | . | . | . | . | . |

Random effects

Table 8

| Number of obs | 2300 |

| Number of groups | 100 |

| Obs per group | |

| min | 23 |

| avg | 23.0 |

| max | 23 |

| R-squared | |

| WithinM | 0.9339 |

| Between | 0.9559 |

| Overall | 0.9503 |

| Wald chi2(5) | |

Table 9

| de_bop | Coefficient | Std. err. | z | P>|z| | [95% conf. interval] | |

| di_bop | .2014334 | .0262227 | 7.68 | 0.000 | .1500378 | |

| dcce | .9460404 | .0058948 | 160.49 | 0.000 | .9344867 | .957594 |

| dcci | -.2033018 | .0254268 | -8.00 | 0.000 | -.2531373 | -.1534662 |

| e_gdp | -.011623 | .0065225 | -1.78 | 0.075 | -.0244069 | .0011609 |

| eb_gdp | -.0149526 | .0111581 | -1.34 | 0.180 | -.0368221 | .0069168 |

| icte | 5.20e-12 | 1.68e-12 | 3.09 | 0.002 | 1.90e-12 | 8.50e-12 |

| _cons | 4.107872 | .480085 | 8.56 | 0.000 | 3.166923 | 5.048821 |

| sigma_u | 3.1124048 | |||||

| sigma_e | 2.4306509 | |||||

| _ rho | .62115963 | |||||

Hausman’s test

Fixed effects

Table 10

| Number of obs | 2300 |

| Number of groups | 100 |

| Obs per group | |

| min | 23 |

| avg | 23.0 |

| max | 23 |

| R-squared | |

| Within | 0.9984 |

| Between | 0.9999 |

| Overall | 0.9998 |

| F(7,2193) | 192267.76 |

| Prob > F | 0.0000 |

| corr(u_i, Xb) | 0.2322 |

Table 11

| trade_gdp | Coefficient | Std. err. | t | P>|t| | [95% conf. interval] | |

| de_bop | .0172684 | .0049265 | 3.51 | 0.000 | .0076074 | |

| di_bop | -.0003896 | .006203 | -0.06 | 0.950 | -.012554 | .0117748 |

| dcce | -.0179175 | .0048645 | -3.68 | 0.000 | -.027457 | -.008378 |

| dcci | .003986 | .0060225 | 0.66 | 0.508 | -.0078243 | .0157964 |

| e_gdp | 1.995633 | .0017712 | 1126.72 | 0.000 | 1.99216 | 1.999106 |

| eb_gdp | -.9973773 | .0027327 | -364.97 | 0.000 | -1.002736 | -.9920182 |

| icte | -4.61e-12 | 3.99e-13 | -11.54 | 0.000 | -5.39e-12 | -3.83e-12 |

| cons | .0497825 | .0939933 | 0.53 | 0.596 | -.1345427 | .2341077 |

| sigma_u | .45761957 | |||||

| sigma_e | .56088885 | |||||

| rho | .3996391 | |||||

| F(99, 2193) | 11.60 | |||||

Random effects

Table 12

| Number of obs | 2300 |

| Number of groups | 100 |

| Obs per group | |

| min | 23 |

| avg | 23.0 |

| max | 23 |

| R-squared | |

| Within | 0.9984 |

| Between | 0.9999 |

| Overall | 0.9998 |

| F(7,2193) | 192267.76 |

| Prob > F | 0.0000 |

| corr(u_i, Xb) | 0.2322 |

Table 13

| trade_gdp | Coefficient | Std. err. | z | P>|z| | [95% conf. interval] | |

| de_bop | .0134695 | .0045647 | 2.95 | 0.003 | .0045228 | |

| di_bop | -.0074051 | .0059312 | -1.25 | 0.212 | -.01903 | .0042197 |

| dcce | -.0138991 | .0045051 | -3.09 | 0.002 | -.0227289 | -.0050693 |

| dcci | .00994 | .0057577 | 1.73 | 0.084 | -.0013448 | .0212249 |

| e_gdp | 1.998037 | .0011554 | 1729.36 | 0.000 | 1.995772 | 2.000301 |

| eb_gdp | -.9993458 | .0022946 | -435.52 | 0.000 | -1.003843 | -.9948484 |

| icte | -3.86e-12 | 3.67e-13 | -10.53 | 0.000 | -4.58e-12 | -3.14e-12 |

| cons | -.0102433 | .0845367 | -0.12 | 0.904 | -.1759323 | .1554457 |

| sigma_u | .36561794 | |||||

| sigma_e | .56088885 | |||||

| rho | .29820342 | |||||

Table 14

| —- Coefficients —- | ||||

| (b) fe | (B) re | (b-B) Difference | sqrt(diag(V_b-V_B)) Std. err. | |

| de_bop | .0172684 | .0134695 | .0037989 | .0018529 |

| di_bop | -.0003896 | -.0074051 | .0070156 | .0018162 |

| dcce | -.0179175 | -.0138991 | -.0040184 | .0018351 |

| dcci | .003986 | .00994 | -.005954 | .0017661 |

| e_gdp | 1.995633 | 1.998037 | -.0024039 | .0013425 |

| eb_gdp | -.9973773 | -.9993458 | .0019685 | .0014841 |

| icte | -4.61e-12 | -3.86e-12 | -7.49e-13 | 1.59e-13 |

| chi2(6) | 21.31 | |||

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0016 | |||

References

Aaronson, S.A., 2024. Trade Agreements and Cross-border Disinformation: Patchwork or Polycentric?. In Global Digital Data Governance (pp. 125-147). Routledge.

Azmeh, S., Foster, C. and Echavarri, J., 2020. The international trade regime and the quest for free digital trade. International Studies Review, 22(3), pp.671-692.

Banalieva, E.R. and Dhanaraj, C., 2019. Internalization theory for the digital economy. Journal of International Business Studies, 50, pp.1372-1387.

Deane, F., Woolmer, E., Shoufeng, C.A.O. and Tranter, K., 2024. Trade in the Digital Age: Agreements to Mitigate Fragmentation. Asian Journal of International Law, 14(1), pp.154-179.

Drori, N., Alessandri, T., Bart, Y. and Herstein, R., 2024. The impact of digitalization on internationalization from an internalization theory lens. Long Range Planning, 57(1), p.102395.

Elsig, M. and Klotz, S., 2021. Digital trade rules in preferential trade agreements: Is there a WTO impact?. Global Policy, 12, pp.25-36.

Jin, Y., 2024. An Empirical Study on the Development Environment of Cross-border E-commerce Logistics in the Global Trade Context: Exploring the Digital Marketing Landscape.

Khan, A., 2023. Rules on Digital Trade in the Light of WTO Agreements. PhD Law Dissertation, School of Law, Zhengzhou University China.

Kim, H.C., 2024. Industrial Digital Transformation and A Proposal to Rebuild Digital Trade Agenda. Journal of World Trade, 58(1).

Peters, M.A., 2023. Digital trade, digital economy and the digital economy partnership agreement (DEPA). Educational Philosophy and Theory, 55(7), pp.747-755.

R. Neufeld and I. Van Damme (eds) The Oxford Handbook on International Trade Law, 2nd edn.(Oxford University Press, 2022), pp.745-767.