Introduction

1.1 Background

The North American Asset Management industry has gone through a various of changes in last decade. These transformations have brought in a drastic change as several of firms are controlling and influencing every aspect of the industry. To understand the current working and trend of the industry one should have a firm knowledge about its contemporary activities since the period of its infancy. One should also be aware of the diverse changes that have led the industry to grow currently and the future state of the industry.

1.2 Objectives of the Study

The main purpose of this dissertation is to holistically examine the nature of competition within the North American Asset Management industry. It will also investigate the framework of traditional strategy which can be used as a leverage and guide to formulate recommendations in ways second and last movers can compete within the industry.

1.3 Inception of the U.S. Asset Management Industry

In every economy function the Asset Management industry provides investors (Pension Funds, Sovereign Wealth Funds, Insurance Companies, Charities, Individuals) with access to professional Investment Management services. These services could also be stated as traditional investments such as stocks and bonds as well as more advanced investments which includes Mutual Funds, Exchange Traded Funds & Non-Listed Investment Vehicles. The industry in the U.S. traces its roots to the Massachusetts Investors Trust, started in 1924 by L. Sherman Adams, Charles H. Learoyd and Ashton L. Carr (Investopedia, 2019). The first company to offer open-ended funds in United States was The Massachusetts Investors Trust. The expense ratio of the was 0.50% (50 basis points). In 1924 the State Street followed suit as well as in 1928 Scudder, Stevens, and Clark were the first to launch a no-load. The year 1928 had proved to be a significant year historically in relation with the mutual fund because the first mutual fund which included bonds and stock known as the Wellington Fund was launched in this year (Investopedia, 2019). The total of 19 open-ended mutual funds was in opposition with the 700 closed-end funds approximately by the year 1929 (Investopedia, 2019).

The stock market crashed in 1929 which was caused due to overconfidence of the industry in the market and public, the stocks bought by the public with easy credits, the enhance interest rates of the government and the panic after the crash which worsened the situation tremendously. This crash triggered the rise of a new dynamic as highly leveraged closed-end funds were wiped out and open-end funds managed to survive (History. (2019).

1.4 The Rise of Regulation

After this huge crash the government regulators took notice of the emerging mutual fund industry. This industry was highly unregulated by generating the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) which is an autonomous central government agency. The SEC is responsible for protecting investors, sustaining an impartial and methodical operation of the securities markets, and facilitating capital formation (Sec.gov, 2019). Moreover, evading the Securities Act of 1933, required all companies that are listed on the stock exchange to follow the outlined requirements in the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (Sec.gov, 2019). The main requirements outlined includes registering any securities recorded on stock exchanges, disclosure, proxy solicitations, and margin and audit requirements (Sec.gov, 2019). The major objective of the requirements was to guarantee a fair environment and restore the confidence within the investor. An Investment Advisers Act was passed by congress in 1940 which was referred to as a U.S. Federal law. This law defined the main responsibility and duty of the investment advisors (Sec.gov, 2019). Prompted in part by a 1935 report to Congress on investment trusts and investment companies which was prepared by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The act provided the legal groundwork for monitoring those who advise pension funds, individuals and institutions on investing (Sec.gov, 2019). It specified the qualification required for being an investment advisor and pointed out the individual registered with state and federal regulators to dispense it. Finally, Congress passed the Investment Company Act of 1940 which put in place additional regulations requiring companies to disclose more information as it pertained to financial statements, stated investment goals, personnel, debt issuance, and directors (Sec.gov, 2019). The goal of the Act was to provide adequate disclosure and to curb the management abuses prevalent during the 1920s and 1930s.

1.5 The First Index Fund

The upsurge of age of regulation did not stunt or exploited the industry as it continued to expand with diversified and complex products offerings. In the late 1990s, the most innovative product within the industry was established or founded by the Index Fund. Wells Fargo Bank (John A. McQuown and William L. Fouse) worked from academic models to develop the principles and techniques leading to index investing but unfortunately, they failed in implementation of the methodology (About.vanguard.com, 2019). Fortunately, the team was able to partner with John Bogle to form the Vanguard Group which is a mutual fund company that is famous for its low-cost index funds and its ownership structure as it was owned by the funds it administered to launch the first index fund (About.vanguard.com, 2019).

1.6 The Rise of Active Management

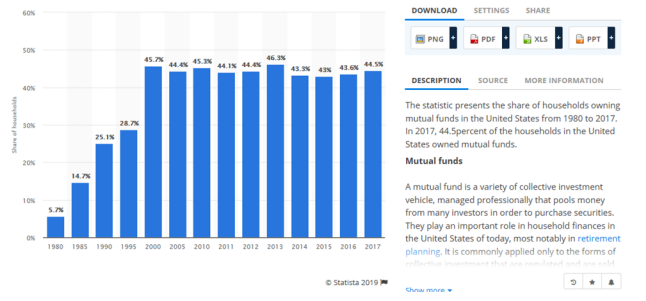

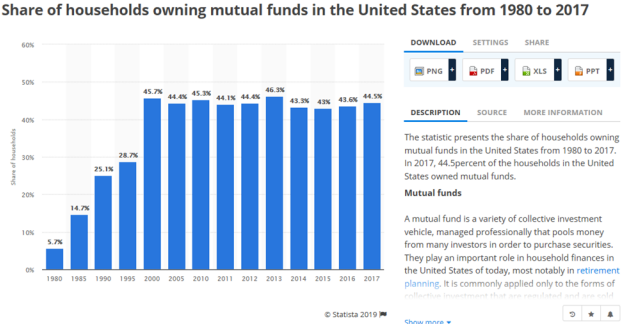

The bull market created in 80’s and 90’s formulated a new approach for managing the asset as Fundamental Analysis, Value investing and Growth Investing. These approaches proved to add value as opposed to index and led to rise in the superstar portfolio managers and names such as Benjamin Graham, Sir John Templeton, T. Rowe Price, Jr, Joel Tillinghast and Peter Lynch. The bull market of the ’90s further helped drive this trend as the super-normal returns achieved above the S&P 500 index during the period led to investors moving flows to their approaches and household ownership of mutual funds increased radically as evidenced by the graph below:

(Statista, 2019)

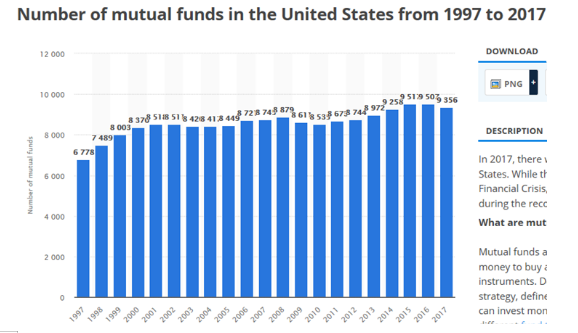

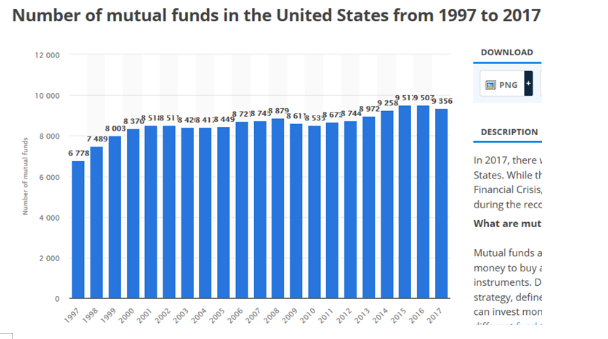

Resultantly, due to the record amount of flows chasing investments the number of Asset Managers offering access, advice and different investment approaches skyrocketed as evidenced below:

(Statista, 2019)

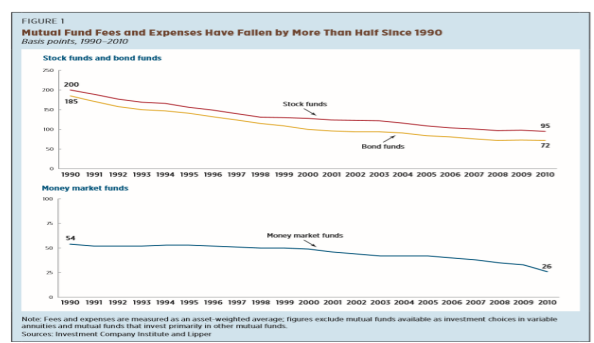

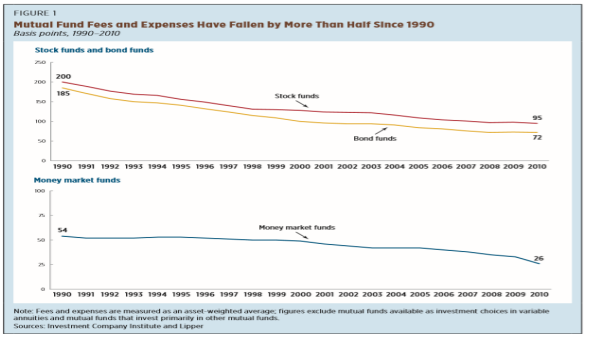

1.7 The Rise of the Fee Age

In this era the Investors were not concerned about fees they were being paid to achieve returns but were more anxious about the returns generated. Keeping this in mind, the Asset Management industry incepted diverse classes in investment share with different fee structures. Its aim was to offer the most cost-efficient product to the investor. According to (Ici.org) in the 1990s investors on average were paid 200 basis points or about $2.00 for every $1000 assets to invest in stock funds. The fees were of two types: one was the sales loads which are one-time fees that investors pay at the time of purchase or during the sale of investments and the second was fund expenses which go to cover expenses such as portfolio management, fund administration, shareholder services, and other operating costs.

Ici.org. (2019).

1.8 Rise of Negative Reputation

In the early 2000’s the Asset Management industry experienced an onslaught of negative press that brought the industry to the focus of legislators. The first scandal was reported as the collapse of L.T.C.M (Long Term Capital) which triggered an industry bailout by the federal reserve bank. It was due to uncertainties that the collapse of the firm would carry substantial counterparty risk to the global financial markets industry (Fleming, M. and Liu, W. (2019). The second scandal occurred around late 2003, known as the trading scandal that shook up the industry. This case when introduced to the public and was cited that the New York Attorney General, Elliot Spitzer had gathered evidences of extensive illegal trading schemes. This illegal scheme had a potential to cost mutual fund shareholders billions of dollars annually. Further development of the case expanded the scope of the Securities Exchange Commission to investigate and focus on approximately 25 asset managers. The investigation resulted in settlement of more than $3.1 billion in fines and restitution (Houge, T. and Wellman, J. 2005). The premise of the case and settlement was twofold. The initial action included late trading while the second action involved market timing (Nytimes.com, 2019). The case was made with the help of the first action that is a number of hedge funds were being allowed to place trades in mutual funds after the cut-off time of 4 pm. This enabled such firms to be able to gain against long term investors as they took advantage of market developments after the close of the day’s trading session. The second focused on another group of hedge funds that we’re able to trade in and out of mutual funds on a daily basis and it allowed them to take advantage of price differences between the market price and the Net Asset Value of mutual funds which is the value that determines the price of a mutual fund (Nytimes.com, 2019).

After the case settlement the SEC soon introduced legislation that aimed at stopping both the practices. To deal with late trading issue the commission proposed a strict 4 p.m. cut-off time for trades and any trades received after the cut-off would have to be placed on the following day. The SEC also adopted rules that would need funds and its advisors to adopt sequence of submission policies. These policies aimed at increasing the supervision of mutual funds operations (Labaton, S. (2019). To deal with the issue of market timing the SEC proposed rules demanding more revelation of the system they value in the securities of their portfolios, as well as funds were also required to impose mandatory redemption fees of up to 2% on investors of the amount redeemed on shares held for five business days or less (Sec.gov.(2019).

The market crash of 2008 saw the S&P 500 decline by 45% and the wealth of the common American decreased drastically. As per the Federal Reserve’s estimation, the first quarter of 2009 was the year Americans noticed their wealth decline by about 1.3 trillion (Money.cnn.com.(2019). In order to stabilize the U.S. economy during this period and prevent the failure of key financial services firms, the Treasury instituted the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). This program costed the U.S. consumer nearly $245 billion spread across five distinct bank programs aimed at achieving different goals for the American banking system (Treasury.gov. (2019). The program was very important but the public started criticizing this scheme extensively as they did not see a reason why the common taxpayer dollars should use to bail out institutions that had found a way to overleverage themselves into bankruptcy. Additionally, the use of the funds by some of the financial services was morally questionable. These funds were used to pay for record bonuses and dividends back to investors while the average American consumer was left to foot the bill. This started leading to a growth in negative sentiment on the whole financial services industry and unfortunately this sentiment boiled over to the investment community. In the investment community the investors who were burnt by the 2008 crash started questioning what they were really paying for as most actively managed funds during the period performed worse than their general indexes, contrary to what investors thought as an active manager was supposed to limit risk in investments during market crash situations.

1.9 After 2008

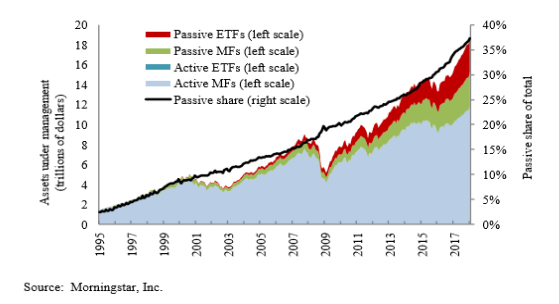

The period since 2008 crash till now has been one of the most disruptive times for the Asset Management industry as the industry has gone through a lot of drastic change. These changes were not minor and has resultant in shaping od unique current working of the industry. The major change that traced its roots to the financial crises is the issue of fees. Before 2008 the issue of fees wasn’t a big consideration but after that year the issue became in the forefront of the investor community. This was because they wanted to understand the real reason for the payment. Additionally a challenge the industry has faced since then is that active managers for the last 12 years have failed to deliver above-market returns due to the U.S. market being in a cyclical bull market, thus further adding fire to the active-passive debate.

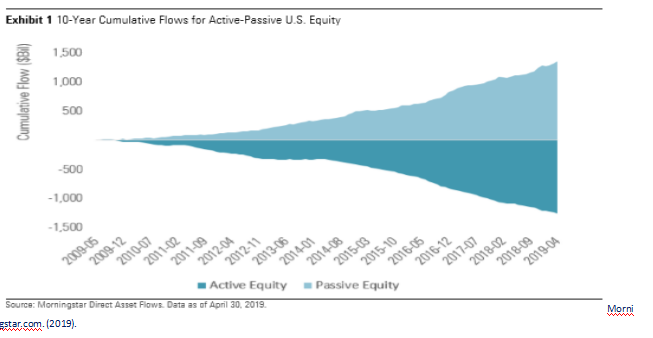

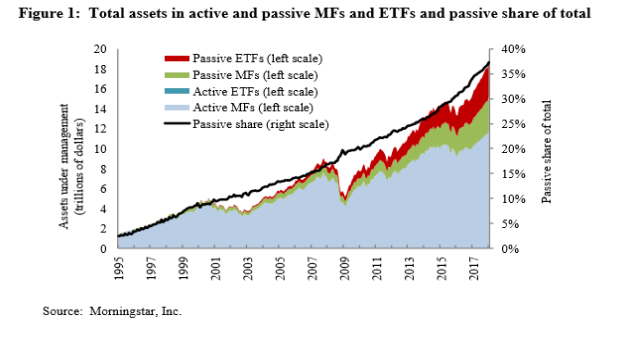

This has led to flowing out of active management into passive management. As per the Federal Reserve, of the U.S., the shift was very evident among the mutual funds (MFs) as shown in Figure 1. In the growth of exchange-traded funds (ETFs), which are largely passive investment vehicles. As of December 2017, passive funds accounted for 37 percent of combined U.S. MF and ETF assets under management (AUM), up from three percent in 1995, and 14 percent in 2005. This shift for MFs and ETFs has occurred across asset classes: Passive funds made up 45 percent of the AUM in equity funds and 26 percent for bond funds at the end of 2017, whereas both shares were less than five percent in 1995 (Boston, 2019).

(Boston, 2019)

In a report by Morningstar on April 30, 2019, was published a passive U.S. equity funds which had an asset of about $4.305 trillion by month-end just $6 billion shy of active U.S. equity funds’ $4.311 trillion. Passive U.S. equity funds closed the gap with more than $39 billion in April inflows, versus more than $22 billion in outflows for their active counterparts. In market share terms (for open-end and exchange-traded funds combined), active U.S. equity funds had 50.04% market share versus passive U.S. equity funds’ 49.96%.

Morningstar.com. (2019).

The relevance of this shift has greatly advanced the competition in the industry as few players have emerged as being dominant against the competition. Therefore, raising the foundation my main research question is to seek answer on how does a second-mover or a last mover compete in this new environment?

1.10 Summary

The relevance of the introduction is to provide the whole background on the NAM Asset Management industry and the different stages the industry has gone. It also tends to focus on the changes that have contributed to where the industry is at present and what the future holds for the industry. This part of the dissertation tries to summaries the different strategies of the firms in the industry used to chase growth and the results of their strategies. The introduction is the backbone my research as the key question is developed in this part of the paper that will leads to formulation of my report. The developed question is stated as how is a Second or Last mover supposed to compete in this new environment?

2. Literature Review

To start developing a framework for exploring how companies in the US Asset Management Industry compete and how changing their competitive strategies could enable them to compete more effectively. I will in this chapter examine the literature on strategic thinking with a focus on literature that addresses strategy, what strategy is and how to develop competitive strategies.

Different market structures yield very different competitive environments, the interaction of the different players within a market tend to shape the level of competition within the industry. Market Structure as defined by Neo-Classical economists refers to characteristics of an economic environment in which businesses operate (Miller, S. P. (2019). The characteristics include factors such as product differentiation, product demand and utilization, market entry requirements, pricing power, and the types and extent of industry competition. These factors tend to determine market structures which are believed to be classified into four types: perfect competition where numerous small companies with the same products compete against each other, monopolistic competition, many companies with slightly different products compete with one another, monopoly market where one company operates with no direct competition and oligopolies where only a few companies compete (Miller, S. P. (2019).

2.1 What is Strategy Isn’t?

As described by Michael Porter in his famous paper, What is Strategy? Companies and managers must be flexible to respond rapidly to market changes (Porter, 1999). Firms are forced to benchmark continuously and outsource aggressively to gain efficiencies, and they are also forced to nurture a few core competencies in the race to stay ahead of rivals (Porter, 1999). Positioning was in the past considered to be the heart of strategy but is found to be too static for today’s dynamic markets and changing technologies (Porter, 1999). According to Michael Porter, in this new age rivals can quickly copy any market position, and any competitive advantage believed to exist is at best temporary (Porter, 1999).

That raises the question, What is Strategy? When defining what strategy is one must start with what strategy isn’t. As described by Michael Porter, Operational Effectiveness is not Strategy unlike popular managerial beliefs, he finds that OE and strategy are both essential to superior performance but the two work in very different ways (Porter, 1999). OE as his paper describes means performing similar activities better than rivals perform them which builds efficiency but OE isn’t all encompassed in efficiency (Porter, 1999). OE, as defined in his paper, refers to any number of practices that allows a company to better utilize its inputs for example by reducing defects in products or developing better products faster (Porter, 1999).

OE requires constant improvement to achieve superior profitability but the challenge is that this is usually not sufficient, the two main reasons as raised by Porter will first be the rapid diffusion of best practices which allows competitors to quickly imitate management techniques, new technologies, input improvements, and superior ways of meeting client needs (Porter, 1999). Porter makes the case that the most generic solutions, which can be used in multiple settings usually diffuse the fastest and he evidences his point by making a case based on the consulting community (Porter, 1999).

The second reason as to why improved OE is insufficient is due to competitive convergence which Porter believes is more subtle (Porter, 1999). The more benchmarking companies perform the more they look alike (Porter, 1999). The more that rivals outsource activities to efficient third parties, the more generic those activities become (Porter, 1999). As rivals imitate one another’s improvements in quality, cycle times, or supplier partnerships, strategies converge and competition becomes a series of races down identical paths that no one can win (Porter, 1999). Competition based on operational effectiveness alone is mutually destructive, leading to wars of attrition that can be arrested only by limiting competition (Porter, 1999).

2.2 Then what is Strategy?

Strategy, as defined by Porter, is the creation of a unique and valuable position, involving a different set of activities (Porter, 1999). The essence of strategic positioning is to choose activities that are different from rivals (Porter, 1999). If the same set of activities were best to produce all varieties, meet all needs, and access all customers, companies could easily shift among them and operational effectiveness would determine performance (Porter, 1999).

2.3 A Sustainable Strategic Position Requires Trade-Offs

Choosing a unique position is not enough to guarantee a sustainable advantage (Porter, 1999). A valuable position will attract imitation by incumbents as competitors can easily reposition themselves to match the superior performer or secondly they can choose to straddle by matching the benefits of a successful position while maintaining their existing strategic position (Porter, 1999). In summary, a strategic position is not sustainable unless there are trade-offs with other positions (Porter, M. E).

2.3 The Importance of Environmental Analysis

All companies operate in a Macro-Economic environment shaped by influences from the economy at large such as population, demographics, societal values, legislation, technological factors and the competitive arena in which the company operates. All these factors are important in defying the character, mix, and nuances of the competitive forces operating in a company’s industry as they are industry-specific.

Traditional strategy theory believes the most efficient tool that should be used to systematically diagnose the principal competitive pressure in a market and assess the strength and importance of each pressure is the 5 forces model of competition by Michael Porter. The model holds that the state of the competition in an industry is a composite of the competitive pressure operating in the 5 areas of the overall market as highlighted below.

(Porter, 2019)

As per Porter, Managers have a constant challenge of defining competition too narrowly while competition for profits goes beyond established industry rivals to include four other competitive forces as well: customers, suppliers, potential entrants, and substitute products (Porter, (2019). The extended rivalry that results from all five forces defines an industry’s structure and shapes the nature of the competitive interaction within an industry (Porter, (2019). As different from one another as industries might appear on the surface, the underlying drivers of profitability are the same (Porter, (2019).

If the forces are intense as per Porter, almost no company earns attractive returns on investment but if the forces are benign, many companies are profitable (Porter, 2019). While many factors influence industry profitability in the short run, industry structure mainly comprised of competitive forces set industry profitability in the long run (Porter, 2019).

The strongest competitive force or forces determine the profitability of an industry and become the most important to strategy formulation (Porter, 2019). Porter highlights five different forces as being key to shaping competition as follows:

The force “Rivalry among Existing Competitors” includes several forms of competition for instance “price discounting, new product introductions, advertising campaigns, and service improvements” Porter, M. E. (2008). High rivalry limits the profitability of an industry. The degree to which rivalry drives down an industry’s profit potential depends, first, on the intensity with which companies compete and, second, on the basis on which they compete (Porter, M. E. (2008).

New Entrants to an Industry change competition as they bring in new capacity and a desire to gain market share that puts pressure on prices, costs, and the rate of investment necessary to compete. The existence of entry barriers limit the number of companies in the industry and therefore influences the ‘Rivalry among Existing Competitors’ (Johnson et al., 2008). Porter (1979) distinguishes between six significant barriers to market entry as follows: (1) Economic of Scale (2) Product Differentiation, (3) Capital Requirements (4) Cost Disadvantages (5) Access to Distribution Channels (6) Government Policy.

The threat of entry puts a cap on the profit potential of an industry. When the threat is high, incumbents must hold down their prices or boost investment to deter new competitors (Porter, 2019). The threat of entry in an industry depends on the height of entry barriers that are present and on the reaction entrants can expect from incumbents. If entry barriers are low and newcomers expect little retaliation from the entrenched competitors, the threat of entry is high and industry profitability is moderated (Porter, M. E. (2008).

Powerful suppliers capture more of the value for themselves by charging higher prices, limiting quality or services, or shifting costs to industry participants. Powerful suppliers, including suppliers of labour, can squeeze profitability out of an industry that is unable to pass on cost increases in its prices. When switching costs are high, industry participants find it hard to play suppliers off against one another (Porter, M. E. (2008).

Powerful customers can capture more value by forcing down prices, demanding better quality or more service (thereby driving up costs), and generally playing industry participants off against one another, all at the expense of industry profitability. Buyers are powerful if they have negotiating leverage relative to industry participants, especially if they are price-sensitive, using their clout primarily to pressure price reductions (Porter, M. E. (2008).

The threat of a substitute is high if they offer an attractive price-performance trade-off to the industry’s product. The better the relative value of the substitute, the tighter is the lid on an industry’s profit potential (Porter, M. E. (2008).

As per Porter, Factors not Forces, determine the industry’s long-run profit potential because it determines how the economic value created by the industry is divided – how much is retained by companies in the industry versus bargained away by customers and suppliers, limited by substitutes, or constrained by potential new entrants (Porter, M. E. (2008).

2.4 Criticisms to Porters Fiver Forces

Grundy in his paper Rethinking and reinventing Michael Porter’s five forces model finds that despite the usefulness of Porters Framework the model has a number of limitations, as it tends to over-stress macro-analysis at the industry level, as opposed to the analysis of more specific product-market segments at a micro-level, It also oversimplifies industry value chains by failing to segment and differentiate the nature of consumers, It additionally tends to encourage the mindset of an ‘industry’ as a specific entity with ongoing boundaries which he believes is less appropriate now where industry boundaries appear to be far more fluid and finally the model appears to be self-contained, thus not being specifically related, for example, to ‘PEST’ factors, or the dynamics of growth in a particular market (Grundy, 2006).

2.5 Five Generic Competitive Strategies

A company’s competitive strategy deals exclusively with the specifics of management’s game plan for competing successfully and securing a competitive advantage over rivals. There are countless variations in the competitive strategies that companies employ as they are tailored to fit each company own circumstances and industry environment. When it comes to strategy selection the main two forces that determine the competitive strategy will be an interplay between the firm’s target market and the type of competitive advantage that the firm is pursuing. Which places a company’s competitive strategy into five different quadrants as displayed below:

(Thompson et al., 2011)

Low-Cost Provider Strategy The aim here is to lead the industry by being able to offer lower overall costs than competitors but not the absolutely lowest possible cost. Successful low-cost leaders are able to use the lower-cost edge to under-price competitors and attract price-sensitive buyers in numbers great enough to increase total profits (Thompson et al., 2011).

Broad Differentiation Strategy The aim here is to be able to differentiate one’s product offering to meet the distinct tastes (preferences & needs) of a set of buyers too diverse to be served by a standardized product or by sellers with identical capabilities. Successful differentiation allows a firm to be able to command premium pricing, increase unit sales and gain buyer loyalty to its unique brand (Thompson et al., 2011).

Best-Cost Provider Strategy The aim here is to be able to give customers more value for their money, this is done by delivering superior value to buyers by satisfying their expectations on factors such as quality, features, performance and beating their expectations on price as compared to competitors offering the same features (Thompson et al., 2011).

Focused (Market Niche) Strategy The aim here is to be able to concentrate attention to a sub-segment of the total market. Focused (Differentiation) Strategy The strategy aims to be able to secure competitive advantage with a product offering that is carefully designed to appeal to the unique preferences and needs of a narrow and well-defined group of buyers. The success of the strategy is dependent on the existence of a buyer segment that is looking for special product attributes or seller capabilities and on a firm’s ability to stand apart from rivals competing in the same target market niche (Thompson et al., 2011).

2.6 Criticisms to Porters Generic Competitive Strategies

As per (Gurău, 2007) paper Porter’s generic strategies: a re-interpretation from a relationship marketing perspective he finds that Mintzberg (1990) places Porter’s work in the ‘positioning school’, which advocates an analytic approach to strategic planning and implementation (Gurău, 2007). Porter outlines that the worst position for a firm is to try to pursue simultaneously more than one competitive strategy. He considers that each type of competitive advantage is independent and specific, and any attempt to combine low-cost leadership and differentiation skills leads the firm’s management in conflicting directions (Gurău, 2007). The paper also argues that in the present competitive market environment in which competitive pressures have multiplied substantially, Porters argument doesn’t hold as some highly differentiated firms are forced to reduce prices to sell their merchandise, because of the fierce competition developed within their strategic group and he additionally finds that Porters work was mostly based on analysis of large corporations acting in mature markets (Gurău, 2007).

Other criticisms to Porter’s theory are attached below:

(Gurău, 2007)

2.7 Strategy Options

Complimentary Strategic Options exist to help firms achieve their selected generic competitive strategy options faster. This is normally done through leveraging the following six options:

(A)Strategic Alliances and Collaborative Partnerships

Are a formal agreement between two or more separate companies in which there is a strategically relevant collaboration of some sort such as the joint collaboration of resources, shared risk, shared control and mutual dependence. The relationship between the partners may be contractual or merely collaborative as the arrangement commonly stops short of formal ownership ties between partners (Thompson et al., 2011).

According to PWC, 59 percent of US chief executives indicate they are planning to initiate a strategic alliance in the next 12 months, a jump of 15 percent over 2015 (Usblogs.pwc.com, 2019). Strategic alliances are beneficial to firms as they allow firms to expedite the development of new products, overcome deficits in their own technical expertise, bring together the personnel and expertise needed to create desirable new skill sets and capabilities, gain economies of scale and finally they allow firms to acquire market access through joint marketing agreements (Usblogs.pwc.com, 2019).

Despite the attractiveness of Strategic Alliances firms are always plagues with the high “divorce rate “among strategic alliances which could be as a result of issues such as diverging objectives and priorities. Historically alliances stand a reasonable chance of helping a firm reduce competitive disadvantages but very rarely have they proved to be a strategic option for gaining a durable competitive edge over rivals (Thompson et al., 2011).

(B) Merge or acquire other companies

M&A are strategically leveraged by firms in situations in which alliances and partnerships don’t go far enough in providing a company with access to needed resources and capabilities as ownership ties are more permanent as opposed to partnership ties, allowing the operations of M&A participants to be tightly integrated and creating more in-house control and autonomy. A merger represents a pooling of equals with the newly created company taking on a new name. While an acquisition is a combination in which one company the acquirer purchases and absorbs the operations of the acquired. The difference between the two strategies is normally as a function of ownership, management control and financial arrangements as opposed to strategy and competitive advantage (Thompson et al., 2011).

Since 2007 in the U.S. the total number of M&A deals was as per Statista 225,712 with a total value 15.8 Trillion dollars (2018. Statista) providing further evidence that most companies favour this path in seeking new growth opportunities, technological capabilities, creation of a stronger brand, or to create a more cost-efficient operation out of the combined companies.

Statista.com

M&A’s look very attractive for managers but historically 70%–90% of acquisitions end up being total failures (MARTIN, 2019). One reason cited for the failure of M&A activities is because of executives who fail to correctly match candidates to the strategic purpose of the deal failing to distinguish between deals that might improve current operations and those that could dramatically transform the company’s growth prospects (Christensen, 2019). As a result, companies pay the wrong price and integrate the acquisition in the wrong way (Christensen, 2019).

There exist two reasons to acquire a company, first to boost performance and help hold on to a premium position and secondly to cut costs. As per (Christensen, 2019) an acquisition that delivers these benefits never changes the company’s trajectory, as CEO’s end up overestimating the value of the boost expected, overpaying and fail at integrating the target (Christensen, 2019). Second, is to reinvent your business model, historically such acquisitions are scarce as very few people know how to identify such targets, how much to pay for them and finally integrate them despite being better targets (Christensen, 2019).

The reason why this is the case is quite simple: companies that focus on what they are going to get from an acquisition are less likely to succeed than those that focus on what they have to give (Martin, 2019). The solution to this issue is that if the acquirer has something that will render an acquired company more competitive the M&A picture changes, premised on the fact the acquisition can’t make the enhancement on its own or with any other acquirer (MARTIN, 2019). An acquirer can improve its targets competitiveness in four ways: by being a smarter provider of growth capital, by providing better managerial oversight, by transferring valuable skills and finally by sharing valuable capabilities (Martin, 2019).

(C) Vertical Integration Strategies

Vertical integration extends a firms competitive and operating scope within the same industry. It mainly involves expanding the firm’s range of activities backward into sources of supply or forward towards end-users. Vertical Integration strategies aim at full-integration or partial-integration both strategies aim to strengthen the firm’s competitive position and boost profitability (Thompson et al., 2011). Vertical Integration has no real payoff profit-wise or strategy-wise unless it produces sufficient cost savings to justify the extra investment, adds materially to a company’s technological and competitive strengths or helps differentiate the company’s product offering (Thompson et al., 2011).

(D) Outsource Selected Value Chain Activities

Outsourcing involves a conscious decision to abandon or forgo attempts to perform certain value chain activities internally and instead to farm them out to outside specialists and strategic allies. The two big drivers for outsourcing are that outsiders can perform certain activities better or cheaper and secondly outsourcing allows a firm to focus its entire strategy on those activities at the center of expertise and that is at the center of its core competencies and that are the most critical to its competitive and financial success (Thompson et al., 2011).

(E) Initiate Offensive Strategic Moves Offensive strategies

Such strategies help a firm to improve its market position and try to build competitive advantage or widen an existing one. The best offensive strategies tend to incorporate several principles: (1) Focusing relentlessly on building competitive advantages and then striving to convert competitive advantages into decisive advantage (2) Employing the element of surprise as opposed to doing what rivals expect and are prepared for (3) Applying resources where rivals are least able to defend themselves (4) Being impatient with the status quo and displaying a strong bias for swift decisive actions to boost a company’s competitive position vis-à-vis rivals (Thompson et al., 2011).

These characteristics are founded on market spaces defined as Red Oceans, which represent all the industries in existence today (Kim, 2005). In Red Oceans industry boundaries are defined and accepted, and the competitive rules of the game are known (Kim, 2005). Companies in such markets try to outperform their rivals to grab a greater share of existing demand. The challenge with such markets is that as the market gets crowded, prospects of profits and growth are reduced which ultimately leads to the commoditization of products and competition becomes bloody (Kim, 2005).

More recent work on offensive strategic moves alludes to the existence of Blue Oceans which are untapped market spaces, which can create new demand and give rise to the opportunity for highly profitable growth (Kim, 2005). The uniqueness of Blue Oceans is the fact that competition is irrelevant as the rules of the game are yet to be defined, company’s creating Blue Oceans never use competition as their benchmarks but instead, they make benchmarks irrelevant by creating a leap in value for both buyers and the company itself (Kim, 2005). Blue Oceans is based on the view that market boundaries and industry structure aren’t given and can be reconstructed by the actions and beliefs of industry players. Finally, Blue Oceans aims to drive costs down while simultaneously driving value up for buyers which achieves a leap in value for both the company and its buyers (Kim, 2005).

(Kim, 2005)

In the paper (Kim, 2005) the case of creating Blue Ocean strategies is further proved by a study that was conducted on the business launches of 108 companies. The study finds that 86% of these launches were line extensions, while a mere 14% were aimed at creating blue oceans but the difference is in business performance as the line extensions in red oceans accounted for 62% of the total revenues, but only delivered 39% of total profits. In contrast, the 14% invested in creating blue oceans delivered 38% of total revenues and a startling 61% of total profits (Kim, 2005).

(F) Employ Defensive Strategic Moves

In competitive markets, all firms are subject to offensive challenges from rivals. The purposes of defensive strategies are to lower the risk of being attacked, weaken the impact of an attack that occurs and influence challengers to aim their efforts at other rivals. While defensive strategies usually enhance a firm’s competitive advantage, they can help fortify its competitive position, protect its most valuable resources and capabilities from imitation and defend whatever competitive advantage it might have (Thompson et al., 2011).

Defensive strategies take many forms and shape but many companies leverage a competitive approach called Judo Strategy that comes from the martial art of Judo. In Judo strategies the aim is for the combatant through emphasizing skill to use the weight and strength of the opponent to their advantage rather than opposing blow directly to blow (Yoffie and Kwak, 2002). The central idea to behind the model is that a challenger into a market must decide how aggressively to enter a market dominated by an incumbent and depending on the share of the market the challenger is looking to capture the incumbent will fight back and will most probably win. With this insight, however, the challenger can induce the incumbent to accommodate their entry by targeting a smaller subset of the market that is unattractive for the incumbent (Yoffie and Kwak, 2002).

The strategy is based on 10 techniques which work closely together to form competitive advantages. The first technique highlighted by (Yoffie and Kwak, 2002) paper is the Puppy Dog Ploy, the essence of the technique is for challengers to keep a low profile and avoid head to head battles as they are too weak to win. The second technique urges challengers to define a competitive space that will allow them to take the lead and in most cases, this space tends to be where the market leader is weak due to overinvestment in the core business. The third technique stresses on the need to follow through fast by combining the first two movement techniques to strengthen one’s position through a constant attack, this allows the challenger to keep the lead gained. The fourth technique focusses on gripping opponents early by offering potential competitors a stake in your success through partnerships, joint ventures or even early equity deals by doing so you can limit your rival’s options and their incentives to develop their capabilities (Yoffie, D. and Kwak, M. (2002).

The fifth technique stresses on the need to avoid tit for tat competitive struggles through gripping, the value of this technique is that you can avoid getting dragged into a pure trial of strength and you can shape competition on your terms. The sixth technique push when pulled advocates for the use of your opponents force or momentum to your advantage this can be achieved by incorporating a competitors products, services or technology into your attack if successful this can help throw them off-balance and confronts them with a choice whether to abandon their initial strategy or to watch it fail. The seventh technique is to practice Ukemi, which is a technique that allows one to fall safely with minimal loss of advantage to return more effectively to the fight. This allows you to lose the battle in the short run to win the war in the long run (Yoffie, D. and Kwak, M. (2002).

The eighth technique is to leverage your opponent’s assets: assets which most companies invest heavily to acquire come with risks which can become a barrier to change by exploiting these barriers one can find the leverage needed to win. The ninth technique is to leverage your opponent’s partners, the belief with this technique is that since many powerful competitors have built up vast networks of suppliers and distributors who are a significant source of strength by being able to exploit differences among them you can turn a rivals partners into false friends. The last technique is to leverage your opponent’s competitors, this view is similar to the old English saying “the friend of my enemy is my friend” by being able to build upon an opponent’s competitors one can craft a strategy will be hard-pressed to match (Yoffie, D. and Kwak, M. (2002).

The paper presents Judo strategies as being 10 core strategies but the authors of the paper make it clear that the menu of choices presented in the paper isn’t a definitive account of Judo Strategies and no listing can capture the wealth of this approach (Yoffie, D. and Kwak, M. (2002). Winning, in the long run, requires the mastery of multiple Judo Strategies and a desire to constantly learn new ways to win. The uniqueness of Judo Strategies is that it allows one to develop a deep understanding of one’s competitors and allows one to understand their potential weaknesses, which isn’t a science and there is not a simple formula for victory. Instead, Judo Strategies demand discipline, creativity, and flexibility to mix and match techniques but the value is that if mastered correctly one can use competitor’s strength to bring them down (Yoffie, D. and Kwak, M. (2002).

2.8 Disruptive Innovation

“Disruption” as per Clayton Christensen, is a process whereby a smaller company with fewer resources can successfully challenge an established incumbent business. This is done by successfully targeting segments that are overlooked by incumbents who focus on improving their products and services for their most demanding and most profitable customers or by creating markets where none existed. By exceeding the needs of these segments incumbents are forced to ignore the needs of other segments which resultantly creates an opportunity for entrants (Christensen, 2019). Entrants that prove to be disruptive, gain a foothold by delivering more suitable functionality, frequently at a lower price and after gaining mastery of the segment they move upmarket delivering the performance that the incumbent’s mainstream customers require while still preserving the advantages that drove success. Once mainstream customers start adopting the entrants’ offerings in volume disruption has occurred (Christensen, 2019).

The paper makes a clear distinction between Disruptive Innovation and Sustaining Innovations which a lot of people confuse as being disruptive in nature. Sustaining Innovations make good products better in the eyes of an incumbents existing customers, these improvements can be incremental advances or major breakthroughs but they enable firms to sell more products to their most profitable customers (Christensen, 2019). Disruptive innovations, on the other hand, are initially considered inferior by most of an incumbent’s customers. Typically, customers are not willing to switch to the new offering merely because it is less expensive. Instead, they wait until its quality rises enough to satisfy them. Once that’s happened, they adopt the new product and happily accept its lower price. This is how disruption drives prices down in a market (Christensen, 2019).

(Christensen, 2019).

Disruptive Innovation as a term is misleading when it is used to refer to a product or service at one fixed point, rather than to the evolution of that product or service over time. Most innovation begins life as a small-scale experiment. Disrupters tend to focus on getting the business model, rather than merely the product right. When they succeed, their movement from the fringe (the low end of the market or a new market) to the mainstream erodes first the incumbents’ market share and then their profitability (Christensen, 2019). This process takes time and incumbents can get quite creative in the defence of their established franchises. The theory of disruption predicts that when an entrant tackles the incumbent competitor’s head-on, offering better products or services, the incumbents will accelerate their innovations to defend their business. Either they will beat back the entrant by offering even better services or products at comparable prices, or one of them will acquire the entrant (Christensen, 2019).

2.9 Radical Innovation

Radical innovations stem from the creation of new knowledge and the commercialization of completely novel ideas or products (Hopp and Antons, 2019). According to the analysis conducted in the paper by scholars of innovation confusing disruptive and radical innovation is problematic as these types of innovation are caused by very different mechanisms and require very different organizational strategies to respond (Hopp, C. and Antons, D. (2019). When businesses are faced with disruptive innovation the answer for incumbent firms lies in a focus on organizational strategies (new business units and new business models). Firms that want to respond successfully to disruptions need to focus on the organization as a whole and need to be willing to eventually cannibalize their own revenues to compete with disruptions successfully (Hopp, C. and Antons, D. (2019).

In contrast, the current research on radical innovation emphasizes dynamic and organizational capabilities (Hopp, C. and Antons, D. (2019). Leveraging core competencies or scaling faster than competitors is important when faced with new technological breakthroughs. Similarly, the literature on radical innovation has a clear focus on people as imagination and the ability to envision the future of technology is important to the generation of the novel ideas required for radical innovation (Hopp, C. and Antons, D. (2019). Therefore, hiring better and more capable employees equips an organization to cope with sudden and drastic change. However, it may not ensure against disruption if an understanding of customers’ needs gets lost in translation. In other words, companies can be great at generating breakthrough ideas yet still suffer from managerial myopia that creates the potential for disruption (Hopp, C. and Antons, D. (2019).

Radical innovation focuses on long-term impact and may involve displacing current products, altering the relationship between customers and suppliers, and creating completely new product categories. In doing so, firms often rely on advancements in technologies to bring their firm to the next level (Hopp, C. and Antons, D. (2019).

2.10 Summary

The purpose of the Literature Review is to showcase different literature that addresses competitive strategy development. The literature addresses the issue of strategy, what strategy is and what it isn’t and the different frameworks that are useful when developing strategy such as environmental scanning (Porters 5 forces) and how to apply the frameworks to generic strategy framework tools and complementary strategy options. Finally, the literature review introduces the idea of Innovation and Radical innovation as being tools to help create sustainable competitive advantages.

3. Methodology Approach

To perform my research and collect the data needed for my results and discussion chapter, I will be leveraging a quantitative approach focussed on two approaches, first a survey and secondly the use of third party data (Morningstar) over-laid on the Herfindahl-Hirschman index methodology which is used to determine market competition levels.

The survey used is a quantitative structured survey which will allow me to collect data from a sample of 50 professionals in the Asset Management Industry who have had experience dealing with the new competitive environment the industry faces by presenting them with a set of structured questions that they had to select from. The sample population for the survey has been created based on former colleagues from my network and additional recommendations from my network who have relevant experience in Asset Management. Additionally, I targeted professionals who work in different corporate functions such as (Marketing, Operations, Sales, Finance, IT, Engineering, Product, R&D, and Business Intelligence) as well key decision-makers in managerial roles to add more dimension to my results and increase the value of the responses.

The second method used was quantitative in approach and focused on the use of the Herfindahl-Hirschman index methodology overlaid on third party Asset Management Industry market data (Morningstar) to be able to analyze the competitive nature of the industry. Both methods used in conjunction with each other will be able to drive my results and discussion.

3.1 The Survey

To gather the opinions from professionals working in Asset Management, the use of the survey was the most appropriate method of data collection as it allowed for a larger reach from a population perspective and also allowed them to be able to record responses quickly with a very minimal impact on time.

The main methods I used to achieve this objective were to distribute the survey to a predetermined list of relationships I had developed during my tenure in the industry. The survey was distributed to a total of 40 professionals and had a response from 28 professionals, a 70% completion rate. The sample size despite being traditionally small was mainly limited by time and also due to the fact I was sending the surveys to respondents in a different geographic region and that presents unique challenges in itself. Regardless, the quality of respondents still would provide me with enough information to test my findings against the literature review.

The questions were generated based on the literature review and based on the problem statement raised in the introduction conclusion. The survey asked 17 questions on the industry but narrowed down to 10 main questions covering topics highlighted below:

1. Work History

2.Demographics

3.Knowledge of Industry

4.Strategy as a concept

5.Competitive Strategies

6.Innovation

The survey was posted on surveymonkey.com an online survey company and also posted on my Linkedin.com to allow for higher visibility from my networks.

3.2 Herfindahl-Hirschman Index

The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (“HHI”) is a statistical measure of concentration in industries (Fraser.stlouisfed.org, 2019). It has achieved an unusual degree of visibility for a statistical index because it’s used by the Department of Justice and the Federal Reserve in the analysis of the competitive effects of mergers and acquisitions (Fraser.stlouisfed.org, 2019). The HHI in this specific case is a useful tool as it further defines the market structure and provides clarity on the nature of competition within the industry (Fraser.stlouisfed.org, 2019).

It is calculated by squaring the market shares of all the firms competing in a market and then summing up the squares as follows:

(Fraser.stlouisfed.org, 2019)

Where:

- S2 is the market share percentage of firm n expressed as a whole number, not a decimal.

The results from the HHI classify markets into three types:

- Unconcentrated Markets: HHI below 1500

- Moderately Concentrated Markets: HHI between 1500 and 2500

- Highly Concentrated Markets: HHI above 2500

One of the most commonly raised challenges to the model is that it might not work in markets with Oligopolies with partially cooperative firms, the challenge with such markets is that the HHI index doesn’t depend on the cooperation level as is the case in symmetric oligopolies (Matsumoto, Merlone and Szidarovszky, 2011).

3.3 Results

To present my research I have created 9 sections to demonstrate my quantitative findings. The initial section will show the analysis of my survey results, which are outlined in my methodology. Secondly, I present the findings of the Herfindahl-Hirschman methodology and will expand on the validity of the methodology and why it’s important in guiding the paper and results. Thirdly, I have then created a synthesis section, which allowed me to compare and contrast the common themes that are presented across the research.

3.4 Overview of survey respondents

Due to the smaller sample size of the survey conducted being able to objectively quantify the validity of the survey respondents is key. As displayed below majority of the survey respondents work in different capacities within the industry and thus allow for diversity of views as it pertains to the industry and this lessens the bias of targeting survey respondents who work in similar functions, but the true value of the survey is highlighted in the roles they play a majority of the respondents work in senior management levels and are on a day to day tasked to make business defining decisions. To validate their responses I purposely question their level of experience and knowledge within the industry and as observed below the majority of the respondents had above-average levels of knowledge of the industry.

Q1. What department do you work in and Role?

Q2. How Familiar are you with the Asset Management Industry?

Q3. Do you think competition has intensified amongst Asset Managers?

When analyzing the general feeling of competition in the Asset Management industry the survey respondents confirmed my hypothesis which was the level of completion within the industry has over the last few years increased dramatically as a result of fee pressures (q4).

This trend is best captured by Mckinnsey research as they report that 2017 marked a year where the growth gap between top- and bottom-quartile firms in North America was 21 percentage points, up 6 points from 2016 (Mckinsey.com, 2019). Interestingly the industry’s largest firms during the year accounted for a disproportionate share of growth, with a set of “trillionaires” generating over 80 percent of all positive organic growth and several making significant gains in share even outside of passive products (Mckinsey.com, 2019). The nature of competition In the Asset Management as per Morningstar is mostly driven by fees (Passive management) which over the 10 years has significantly risen in popularity and has been able to gain market share, what is surprising about this change is that the shift to passive funds hasn’t come with much growth for the industry (Morningstar.com, 2019).

Q4.Do you believe one of the strategies will dominate the industry in the future?

Since the nature of competition in the industry is majority fee oriented the survey wished to identify their views of what the future of the industry would look like and majority of the respondents (56%) envisioned a future where both passive and active management would coexist side by side as opposed to any of the single approaches dominating the industry in the future while the other respondents saw that passive management in the future would play a more significant role in the future as opposed to active management.

This observation is contrary to PwC’s research as they hold the belief that while assets under management (AUM) of both active and passive funds is expected to increase, passive funds are set to see the fastest growth over the next ten years, highlighting the potential for future expansion in the ETF industry. PwC forecasts that funds under passive management will make large gains in market share, rising from 17% of overall global AUM in 2016 to 25% in 2025 while AUM in Actively managed funds will decrease from 71% in 2016 to 60% by 2025 globally (Pwc.com, 2019).

Q5.Do you see legislation driving change in the Industry?

Continuing with the theme of competitive forces in the industry, the survey revealed that 56% of the respondents say that the change in the legislative environment wasn’t a very significant driver of change in the industry and its effects were predominantly about the same as in the past, this was a contrast to some of the other respondents (25%) who saw legislation as a tool for driving positive change in the industry (18%) who saw legislation as being worse for the industry. This was contrary to expectations as the industry over the last 10 years has been going through advanced legislative changes and expectations were this would be a factor that the respondents would find to be of concern.

Q6. How important is a firm’s strategy in this new Industry environment?

After defying the current competitive landscape the survey aimed at measuring the respondent’s attitudes to strategy, majority of the respondents in the survey (54%) viewed a firm’s competitive strategy being of the single most importance to a firm’s success in the new environment while the other respondents had a slightly lower conviction in strategy being of sole importance in competition. What was of interest is that none of the respondents had a negative response record as it pertains to strategy.

Q7. Do you believe consumers yield power in the industry?

Since strategy was proven by the respondents to be essential, the next question was set to understand their views as it pertained to the consumer power in the industry and 86% of the respondents identified consumers as yielding significant power in the industry. This was in line with expectations as the industry has as a result of the rise of passive management and their relatively low fee structure shifted all the power to consumers as switching costs are extremely low and in some cases none existent.

Q8. Do you think the industry faces a threat of new entrants?

Majority of the respondents to the question (71%) saw the industry as being open to new entrants while the rest (29%) found the industry being protected to new entrants. This response is contrary to traditional beliefs as the industry has a very high capital entry barrier which would be expected to discourage new entrants from entering the industry. But the response is in line with State Street who conducted a similar survey that reported (79%) of the respondents in their survey foresaw direct competition from non-traditional market entrants (Google, Apple, Alibaba) (Statestreet.com, 2019).

Q9. For firms in the industry which competitive strategies do you think will prove fruitful?

On the theme of competition the question was aimed at identifying the respondents view on competitive strategies and which nature of strategies they believe would have the most amount of value for an asset manager in this environment, majority of the respondents (32.14%) favoured the pursuit of overall low cost strategies while the next favourable was the pursuit of focused differentiation strategies (25%).

Q10. For firms in the industry which complementary strategy options do you think will prove fruitful?

On the same theme of competition the question was aimed at identifying the respondents view on complementary strategy options and which nature of strategies they believe would have the most amount of value for an asset manager in this environment, majority of the respondents favoured the following three options (28% Employ Defensive Strategic Moves, 25% Initiate Offensive Strategic Moves, 22% Mergers & Acquisitions)

Q11. Do you think there is room for disruptive innovation in the industry?

Finally, when the respondents were prompted as to whether the industry has room for innovation majority of the respondents (86%) found this to be highly likely, while 10% of the respondents were not too sure and only 3% of the respondents felt that this was unlikely.

3.5 Herfindahl-Hirschman Index

The results of the index methodology applied to the Passive Asset Management Industry generates a score of 2500 and when the index is applied to the Active Management Industry the results generate a score of 514. The results show that the Passive Asset Management industry is highly concentrated while the Active Management industry is un-concentrated.

3.6 Summary

The function of the methodology part of the paper was to evaluate the main research question that emerges at the end of the introduction, which is how can a second or last mover in the NAM Asset Management industry compete in light of the nature of competition that is currently being observed. The research that was conducted was in the form of an online survey paired with Herfindahl-Hirschman Index methodology on industry data and the study recognized that there are both advantages and disadvantages of the research method used and this was considered when analyzing the results.

4. Discussion of Results

4.1 Purpose

The purpose of this section is to be able to discuss the results of the survey and compare and contrast the findings to the literature review and the background on the industry to guide recommendations.

4.2 Discussion

The results of the survey were refreshing as the information and results were gathered first hand from practitioners in the industry and have a chance to collect responses from them was unique as they all presented very different viewpoints. The survey was aimed at being able to gauge the industry’s view as it pertained to traditional strategy frameworks and how they could be leveraged within the industry as illustrated by the literature review. It’s very clear from the responses recorded that the Asset Management industry is going through a period of drastic change and everyone is in unison that the level of industry has drastically increased as opposed to the past and that success in the future will be driven by firms that are able to strategically position themselves in light of this new environment.

As highlighted in the introduction the nature of competition in the industry has changed over the last 10 years and the new competitive landscape is being driven mostly as a result of fees in this meaning that consumers have a higher reluctance to pay for investment delivery and would rather result in investing in passive investment instruments that are cheaper and still offer them exposure to the same asset classes as opposed to paying high fees to gain the same exposure this is further captured by the following chart from Morningstar highlighting the trend in the industry as it pertains to fees since 2000.

Morningstar.com. (2019)

This change in the industry has come with new realities as firms are forced to change their business models to remain competitive in the new landscape as the new environment comes with new realities as it pertains to profitability as a move to lower fees indicates that the industry is going through commoditization and might be maturing. Prompting the main reason for the paper which is in light of this new environment how is a second/last mover supposed to compete against the first movers who have in a matter of years gained great market share against peers?

The research into the topic also brings forth very interesting insights as it pertains to the future of the industry and where the respondents see the industry going in the future as the results showed they believed that the future will be an industry where both Active and Passive management existed side by side together which could be argued as the current trend clearly identifies that the rise in passive management and the pace in its rise indicates that the industry will be in the future dominated by passive management, this question could be further investigated in the future as per the limitations of my survey I had a lower sample size and fewer resources that could better gauge the question and come up with better concussive results.

Legislation within the whole Financial Services industry is a very sensitive topic as the industry since 2008 has seen more and more legislation enacted to help curtail risk in the industry. In the survey, the respondent’s responses as it pertained to Legislation and it is a driver for change indicated that majority saw the change in Legislation as having an average effect on the industry and its effects as a driver to change were normal. This is contrary to expectations as one of the key drivers to the move to passive has been from an industry perspective been driven by legislation that aimed at making the issue of fee transparency more clear to investors and the results could have been recorded as such as the industry is already transforming as a result of the change. The results obtained could be driven by the stage the industry is in as it pertains to legislation and leads one to assume the respondents didn’t believe that there was anything that could be done to change legislation.

The power the consumer holds within the industry is unsurmountable proven by the change being experienced within the industry as the rise in passive management alludes to the fact that industry switching costs are extremely low and consumers have all the power, this is also captured by the survey respondents who share the same response. This proves that when in crafting strategy in the industry the consumer must be at the forefront of all strategic decisions.

The likelihood of new entrants into the industry as indicated by the respondents is very high as the majority did indicate that new entrants do have a place in the industry. This response in line with other industry surveys that indicated industry leaders foresaw the entry/direct competition from non-traditional market entrants (Google, Alibaba, Apple) (Statestreet.com. (2019).

The sequence of questions addressed above were aimed at being able to establish the link between porters five forces and the industry and as per the responses recorded and the introduction which gives background on the industry it’s clear that the nature of competition is intense and survival in the industry is highly dependent on how well a firm can fend of current competition and secondly how well a firm can reconfigure its business model in the future.

In light of this environmental/industry information, it’s clear that competitive strategies are important to firms in the industry but the challenge for any firm in a competitive industry is to determine which strategies will yield the most amount of benefit. In the survey, the respondents indicated that by leveraging the following strategies could prove fruitful for any firm in the industry pursuing an overall low-cost strategy or pursuing a focused differentiation strategy. This result could be highly attributed to the industry change as the current environment has highly favoured the pursuit of low-cost strategies and it could be used to deduce the fact that in the future cost will be the most key competitive advantage firms can compete on or differentiation to some extent.

In addition to this, the respondents when asked about complementary strategy options that firms in the industry could leverage when competing for the majority of the respondents favoured the following three options (Employ Defensive Strategic Moves, Initiate Offensive Strategic Moves, Mergers & Acquisitions). This is in line with the literature review section on complementary strategy options and will help in the formation of my recommendation as I will have more commentary on these ideas.

Disruption in the industry has been a topic discussed by many industry leaders such as EY who foresee disruption in the industry as being shaped by the rise in robotics and AI which will in the future change how firms communicate with the end-user. In the survey majority of the respondents indicated that the industry was poised for innovation which seems to be a plausible result.

Finally, the application of HHI methodology to the industry draws up a picture of the industry that is contrary to the respondent’s belief of competition according to the index the Passive Asset Management Industry generates a score of 2500 (Concentrated) and when the index is applied to the Active Management Industry the results generate a score of 514 (Unconcentrated) which is contrary to the respondents as they believed that competition in the future of the industry should be marked by firms pursuing low-cost strategies (Passive Management).

4.3 Summary

The survey results supported a number of frameworks in the literature review which have been discussed in this section. Some new findings were discovered about competition in the industry that was uncovered by the HHI methodology that drew some contrast to the survey. These findings have been discussed to generate recommendations for second movers in the Asset Management industry.

5. Recommendations

5.1 Purpose

The purpose of this section is to provide recommendations for second movers in the Asset Management industry based on the literature review and the data collected on competition in the Industry. These recommendations are suggested in light of the current industry environment.

5.2 Recommendation

All throughout the paper the major theme that has emerged is that the industry is going through a drastic level of change and a firm’s strategy is the more and more important in withering the change. It’s evident that the level of competition in the industry is high as the market participants are aggressively jockeying for different positions in the industry and it’s clear that some firms are uniquely positioned in the industry as evidenced by the rise of the top 10 who shape the industry competitively.

Morningstar.com. (2019).

From the survey, a couple of key themes emerged which will be the premise of my recommendations namely

5.3 Overall low-cost strategies

It’s clear that the nature of competition in the industry is currently being driven by a move to low cost investment vehicles (Passive Management) thus for a second-mover in the industry a move to providing access to Passive Management vehicles could help the firm protect its position and even enhance its market share as opposed to only offering Active Management vehicles. This belief is also shared by Morningstar Research who since 2000 report that the cheapest funds (those whose fees rank within the bottom 20% of their category group) have managed to see record flows as opposed to peers. In 2018, low-cost providers saw net inflows of $605 billion, 97% of it went into the cheapest of the cheap, the least costly 10% of all funds. In contrast, they report that the remaining 80% have been haemorrhaging assets as in 2018 they saw a record $478 billion in outflows (Morningstar.com. (2019).

Morningstar.com. (2019).

5.4 Focused Differentiation Strategy

The essence of focused differentiation strategies is concentrating attention on a narrow piece of the total market or industry where product/service uniqueness attracts buyers looking for such features. Success in such markets depends on the existence of a buyer segment that is looking for special product attributes and on a firm’s ability to stand apart from rivals competing in the same target market niche. In this case, this would mean looking to specialize in segments of the industry that attract a need for more specialization of the investment process that would attract premium pricing. In the asset management industry, this could mean moving into specialized Asset Classes such as Alternative Investments or Thematic Areas of the industry such as E.S.G. (Environmental Social Governance) or Sustainable Investing.

Sustainable investing is an investment approach that considers environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors in portfolio selection and management. What’s unique about this market is that global investments into the market have been increasing and as of 2018 the market reached $30.7 trillion globally. In the U.S. as highlighted below this market has been continuously growing and from 2016-2018 the market grew by 38% and is forecasted to grow faster in the future due to Millennials and Generation-X.

(Gsi-alliance.org, 2019)

Alternative Investments are a class of investments that are considered to be outside the mainstream of traditional investments. Total assets under management (AUM) within alternatives have soared from $1 trillion in 1999 to more than $7 trillion in 2014 which is twice the rate of traditional assets from 2005-2013 moreover the growth captured (CAGR) is double that of traditional investments (McKinsey & Company, 2019). Furthermore, PWC expects AUM in alternatives to nearly doubled again to $13 trillion by 2020 (PwC, 2019). What makes this market niche is that traditional investors play a smaller role as the process to invest is more regulated legislatively and only Accredited Investors can access such investments.

(McKinsey & Company, 2019)

5.5 Mergers & Acquisitions

M&A presents unique chances for firms looking for new growth opportunities, technological capabilities, creation of a stronger brand, or to create a more cost-efficient operation out of the combined companies. Mergers and acquisitions among investment managers as per FT in 2017 reached levels not seen since the aftermath of the financial crisis, this is being driven by the macro challenges the industry is facing, including deteriorating economics, distributor consolidation, the need for new capabilities, and a shifting value chain. The total value of announced deals hit $40.9bn, the highest since 2009 but the volume of transactions fell to its lowest since 2006, reflecting a trend of fewer but larger deals among mid-tier players, according to numbers compiled by FT (Ft.com, 2019). According to FT, the nature of mergers being seen reveal a trend that is characterized as being a convergence of weak companies that have suffered significant net outflows, thus the M&A transactions are aimed at making them bigger, more diverse to help offset the pressure on fees but the challenge is that the activity is from a position of weakness (Ft.com, 2019).

(Ft.com, 2019)

This trend is expected to increase in the future as the same pressures will not magically disappear, thus being said the question becomes how do you make M&A transactions successful? According to Deloitte successful transactions in the industry will be centered on the following types of acquisitions:

- Transformative scale acquisitions

• Pure consolidating deals

• Capability-based transactions

• Value chain-extending transactions

And for the transactions to be successful management needs to be able to deliver clear cost and revenue synergies that unlock investment capital, leverage data, and technology to drive competitive advantage and finally position the new entity in response to the legislative environment. The key to achieving the above goals is in how post-merger integration is handled as the industry has traditionally never dealt with this issue historically (Deloitte United States, 2019).

5.6 Initiate Offensive Strategic Moves

Traditional strategic theory as highlighted in the literature review is founded on Red Oceans which defines the majority of the industries in existence today. In Red Oceans industry boundaries are defined and accepted, and the competitive rules of the game are known. Companies in such markets try to outperform their rivals to grab a greater share of existing demand. The challenge with such markets is that as the market gets crowded, prospects of profits and growth are reduced which ultimately leads to the commoditization of products and competition becomes bloody (Kim, 2005).

More recent work on offensive strategic moves alludes to the existence of Blue Oceans which are untapped market spaces, which can create new demand and give rise to the opportunity for highly profitable growth (Kim, 2005). The uniqueness of Blue Oceans is the fact that competition is irrelevant as the rules of the game are yet to be defined, company’s creating Blue Oceans never use competition as their benchmarks but instead, they make benchmarks irrelevant by creating a leap in value for both buyers and the company itself (Kim, 2005). Blue Oceans are based on the view that market boundaries and industry structure aren’t given and can be reconstructed by the actions and beliefs of industry players. Finally, Blue Oceans aims to drive costs down while simultaneously driving value up for buyers which achieves a leap in value for both the company and its buyers (Kim, 2005).