1. Introduction

Shark bites are

common and are observed frequently in

beaches. The Recife’s metropolitan region in Brazil has experienced

high shark attack rates, between 1992 and 2011. Fifty-five incidents were noted regarding the shark attacks (Hazin

& Afonso, 2014). To reduce the death rate by shark

attacks, a strategy was introduced by the government. Under this strategy,

shark nets were introduced to kill sharks. It is a submerged net placed around crowded beaches mostly to

protect beachgoers. Different types of shark nets are used, one of which is gillnets which

targets the sharks and capture them by entanglement. Not only sharks, but other marine species also get

entangled in the gillnets. About 74% odontocete species, 66% pinnepeds, 64%

mysticetes, sirenians and mustelids become the bycatch of gillnets over the

past 20 years (Atkins, 2016).

2. Analysis

2.1 Human safety -Do shark nets really protect humans from shark attacks?

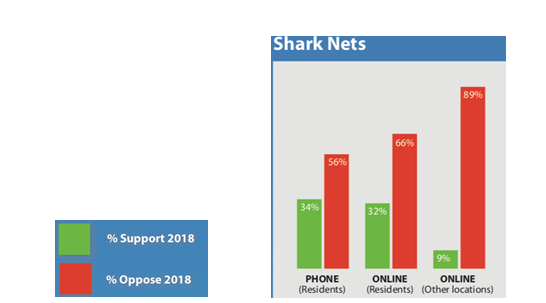

Unprovoked attacks by sharks is the biggest fear of human, especially in case of beachgoers. Most of the number of people getting injured or killed due to shark attacks are swimmers and surfers. According to Lemahieu et al. (2017), between 2011 and 2013, eight people were killed by the shark bites in Reunion Island’s West Coast. There were many cases reported regarding shark attacks. To reduce the rate of attacks by shark, shark nets were introduced by the government. It was designed to kill sharks by entangling them into shark nets. It is placed around the beaches to minimise the contact between human and shark (Shark management, 2019). After the installation of shark nets in beaches, the number of shark attack is reduced drastically (Gibbs & Warren, 2015). As stated above, shark nets were introduced to kill sharks, but it failed to do so. It only captures shark by entangling them in the shark nets. Hence, a new strategy was proposed by the government that works on the principle of capture and kill. This strategy is named as “shark hazard mitigation strategy” (Department of premier and cabinet, 2019). Under this strategy, they were killed cruelly by the people after capturing them. According to a study done by Gibbs and Warren (2014), on January 24, 2014, after capturing a 3m Tiger Galeocerdocuvier (Tiger Shark), it was killed brutally by shooting four times by the rifle in the shark’s head by the government’s employee and then the body was dumped alongshore. Although the number of people getting injured is minimised, shark nets do not provide full protection against shark bites. To lessen the interaction between shark and beach-goers some other techniques are also introduced by the government known as shark culling and shark spotting (Curtis, 2012). This strategy imposed negative impact on the demographic population of shark. As high rate of shark killing destroys the marine ecosystem, but neither the government nor the local people consider it a serious issue. According to Gibbs and Warren (2015), public perception about killing shark is in favour of the government. Beach-goers often encounter sharks and to minimise the risk of shark bites and shark attacks; they support the program initiated by the shark hazard management to capture and then kill the sharks. According to a study done by Neff and Yang (2013), in 1996 a survey was conducted based on shark killing. At that time out of total respondents, only 30% mentioned that shark killing is a major issue. Another survey conducted in 2003 have an opposite result, it was found that 80% of the respondents feel that the population of shark is too high and they must be killed to protect humans. A survey was conducted by the government about the attitude of people towards shark nets. The survey was done over phone and online. From the result obtained by the survey, it can be concluded that there are very less number of supporters of shark nets as compared to that of the people that opposes the strategy (Department of primary industries, 2019).

Figure: Diagrammatic representation of survey done based on people’s attitude towards shark nets

Source: (Department of primary industries, 2019)

2.2 Shark nets bycatch – are sharks the only victim of shark nets?

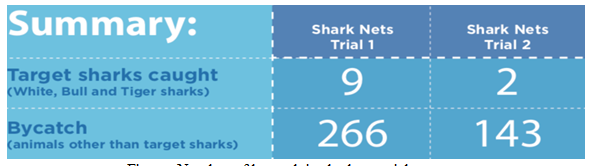

Shark nets are invented to either kill sharks or to capture them by entanglement and minimise the number of shark attacks (Shark management, 2019). Even though it is designed to catch sharks, they are not the only victim. There are many other endangered water species which becomes by-catch in these nets. In a study done by Atkins, Cliff and Pillay (2013), it is mentioned that instead of a shark, Sousa plumbea (Humpback Dolphins) are caught multiple times in KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa. By these, the mortality rate of humpback dolphins has increased rapidly, making it an endangered species. There are many endangered and threatened species such as dolphins, dugongs, whales and sea turtles which becomes frequent bycatch. Another study conducted by Lane et al.(2014), suggests that in KwaZulu-natal Coast of South Africa, five Indo-Pacific Sousa plumbea (Humpback Dolphins) and thirty-five Indian ocean Tursiopsaduncus (Bottlenose Dolphins) between 2010 and 2012. Apart from that, there are some species of sharks which are counted into endangered and threatened species that are getting killed by shark nets, which is a massive loss to the ecosystem. In a study conducted by O’Connell et al. (2014), it is mentioned that shark nets have impacted negatively on the migratory and local shark population. Carcharodon carcharias (White shark) is a protected species, that suffers from mortality after installation of shark nets. Neophocacinerea (Australian sea lions) is one also one of the protected species having small breeding colonies. These sea lions are one of those marine species that becomes the frequent by-catch of shark nets and is now on the verge of becoming threatened species (Hamer et al. 2013). To examine the rate of bycatch, two shark net trial was performed by the government. In the first shark net trial, only nine sharks were caught, whereas the number of bycatch is 266. In the second trial, only 2 sharks were captured and 143 other animals were caught (Department of primary industries, 2019). From the result obtained by conducting the survey, it can be concluded that the number of bycatch is more than that of target animals.

Figure: Number of bycatch in shark net trials

Source: (Department of primary industries, 2019)

3. Conclusion

From the above report, it can be concluded that the cases of shark bites are prevalent in Australia, and many beachgoers were heavily injured or killed by these attacks. To lower the rate of shark attacks, shark nets are introduced by the government. The outcome of these gillnets were found to be less effective as they were only getting entangled but not killed. Hence, another strategy was formulated named as shark hazard mitigation strategy. According to this strategy, sharks were only captured by using these nets and are killed afterwards. This strategy is proved to be more effective in killing sharks, but sharks are not the only one to get entangled in the nets. A Huge number of other species becomes bycatch of the net and get killed. The Death rate of marine species increased after the installation of these nets, which damages the marine ecosystem.

4. Reference

Atkins, S., Cantor, M., Pillay, N., Cliff, G., Keith, M., & Parra, G. J. (2016). Net loss of endangered humpback dolphins: integrating residency, site fidelity, and bycatch in shark nets. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 555, 249-260.

Atkins, S., Cliff, G., & Pillay, N. (2013). Multiple captures of humpback dolphins (Sousa plumbea) in the KwaZulu-Natal shark nets, South Africa. Aquatic Mammals, 39(4), 397.

Curtis, T. H., Bruce, B. D., Cliff, G., Dudley, S. F., Klimley, A. P., Kock, A., … & Lowe, C. G. (2012). Responding to the risk of White Shark attack. Global Perspectives on the Biology and Life History of the White Shark. CRC Press, 477-510.

Department of premier and cabinet. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.dpc.wa.gov.au/publications/documents/wa%20gov%20shms_updated180716_on%20website.pdf

Department of primary industries. (2019). North Coast shark net trial. Retrieved from https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fishing/sharks/management/shark-net-trial

Gibbs, L., & Warren, A. (2014). Killing Sharks: cultures and politics of encounter and the sea. Australian Geographer, 45(2), 101-107. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2014.899023

Gibbs, L., & Warren, A. (2015). Transforming shark hazard policy: Learning from ocean users and shark encounter in Western Australia. Marine Policy, 58, 116-124.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2015.04.014

Hamer, D. J., Goldsworthy, S. D., Costa, D. P., Fowler, S. L., Page, B., & Sumner, M. D. (2013). The endangered Australian sea lion extensively overlaps with and regularly becomes by-catch in demersal shark gill-nets in South Australian shelf waters. Biological Conservation, 157, 386-400.

Hazin, F. H. V., &Afonso, A. S. (2014). A green strategy for shark attack mitigation off Recife, Brazil. Animal Conservation, 17(4), 287-296.

Lane, E. P., De Wet, M., Thompson, P., Siebert, U., Wohlsein, P., &Plön, S. (2014). A systematic health assessment of Indian ocean bottlenose (Tursiopsaduncus) and Indo-Pacific humpback (Sousa plumbea) dolphins incidentally caught in shark nets off the KwaZulu-Natal coast, South Africa. PloS one, 9(9), e107038.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0107038

Lemahieu, A., Blaison, A., Crochelet, E., Bertrand, G., Pennober, G., & Soria, M. (2017). Human-shark interactions: The case study of Reunion island in the south-west Indian Ocean. Ocean Coastal Management, 136,73-8 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2016.11.020

Neff, C. L., & Yang, J. Y. (2013). Shark bites and public attitudes: policy implications from the first before and after shark bite survey. Marine Policy, 38, 545-547.

O’Connell, C. P., Andreotti, S., Rutzen, M., Meÿer, M., Matthee, C. A., & He, P. (2014). Effects of the Sharksafe barrier on white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) behavior and its implications for future conservation technologies. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 460, 37-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2014.06.004

Shark management. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fishing/sharks/management